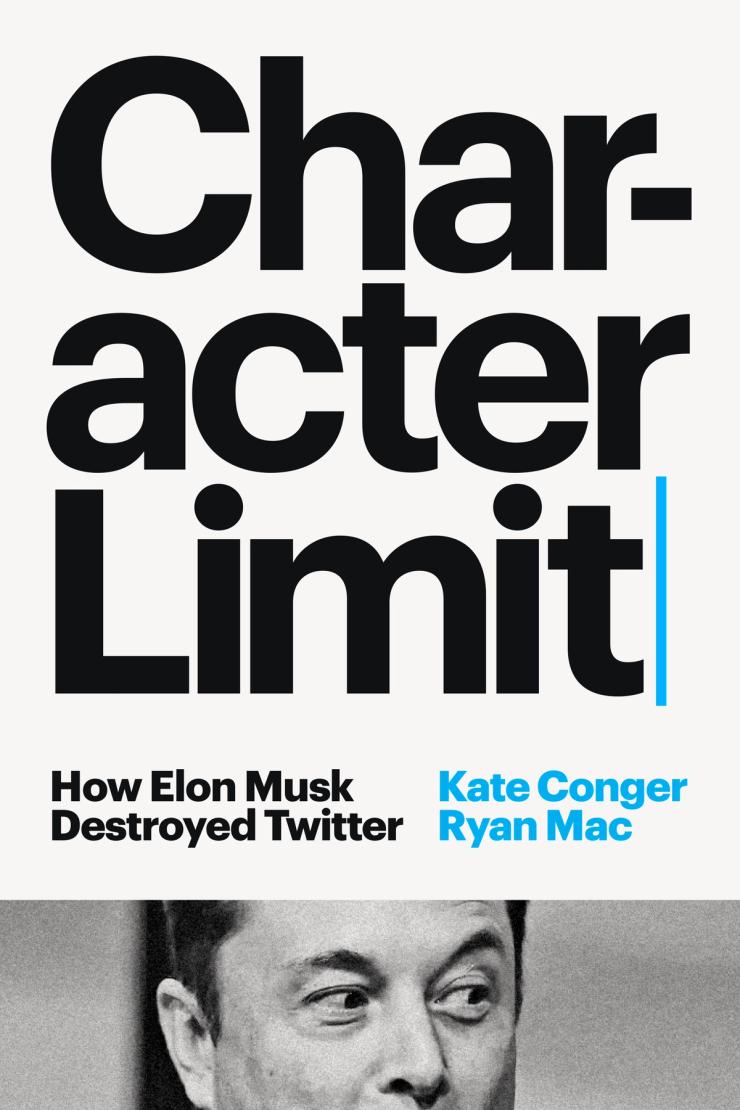

Semaforums are occasional short Q&As with authors and other interesting figures, edited and compressed for space and clarity. Kate Conger and Ryan Mac are tech reporters for The New York Times and authors of the new book “Character Limit.” They spoke here with Ben Smith and other Semafor staffers.

Ben Smith: This played out so much in public, a lot of it on Twitter. How did you think about a story that navigates behind the scenes, when so much is in front of the scenes?

Ryan Mac: I think they gave us an opportunity. Because it was so public, there was like a daily drumbeat of stories — “Elon fires these people today,” or “the site shut down,” or “this employee went rogue.” It was so much to do that I don’t think it gave anyone an opportunity to do a deep dive. There weren’t any big magazine stories or New Yorker features on a takeover or the deal itself. And so I think because of that, it left kind of a hole for us to fill.

And on top of that, like there was just so much material that anyone could have covered. We have a lot of scenes in the book that are text messages and text messages, like the internal dealmaking.

There’s a scene in there of Elon at Berghain, this club in Berlin, trying to text the board members as he’s getting rejected from the club, whether or not he should join the board at Twitter. If people had just lined up the tweets with the timing of the text messages, you would have seen this incredible storyline. But because people were so focused on the immediacy of it, and trying to break the news when it came out, no one ever went back.

Ben: Why did he get turned away from the club?

Ryan: I don’t think we ever got to the bottom of that. We didn’t send anyone to Berlin’s nightclub scene to find out. But he was tweeting about it. He got rejected, as many people do from the lines of Berghain. Within a couple hours, he was on his plane back home, trying to figure out if he should join the Twitter board.

Ben: The first, maybe, 100 pages of the book are set in the “before” times, when Twitter employees are trying to create an infrastructure for misinformation — for safety, as they see it. But it sounds, from your reporting, like they’re themselves growing a little uncomfortable with what they’ve built around throwing people off the platform and trying to control speech and guarantee free speech at the same time.

I read it and I thought, “I think that Kate and Ryan are more sympathetic to the Elon critique of Twitter now than they used to be.” But I don’t know if that’s true. Not his conduct after, but the right-wing diagnosis that Twitter had thrown too many people off, was censoring too much speech — do you think there’s something to that?

Kate Conger: Something that really bothered me in the telling of this story as it played out, was that it really simplified what was going on at Twitter, and the story became sort of these White Knights of the Old Company fighting off this evil character in Elon. And I think that that really flattened and oversimplified what was happening at Twitter. And it was really important to me that we capture some of the mismanagement and some of the problems in Twitter 1.0 that set the company up to be taken over.

I don’t know that I would describe myself as sympathetic to the right-wing complaint that Twitter banned too many people, removed too much content. But I do think there was a consensus among the three CEOs that we cover in the book, Jack [Dorsey], Parag [Agrawal], and then Elon, that the way that Twitter was dealing with content moderation wasn’t working and would not scale over time.

Ben: The original sin, in some ways, for a lot of conservative criticism is the Hunter Biden laptop [story]. What do you think is misunderstood about how Twitter handled that?

Kate: I don’t know if this is misunderstood anymore, but what I think was misunderstood at the time was how much pressure Twitter had been put under to prepare for a second coming of Russian interference in that election, and how much stress and anxiety that put on this staff. So in that moment, when that story broke, and there was a very low level of information about where the laptop had originated from and how it had made its way into the media — there was that kind of looming fear of foreign interference that influenced a lot of the decision-making around that.

Ryan: We see that now with Mark Zuckerberg’s letter the other day, he is talking about that and kind of using that as a crutch, an explanation for why he did it. And also that kind of became a moment for Dorsey himself to kind of split with his staff. There was a lot of blame, even internally at Twitter at the time, and Jack tried to cleave himself off from the decision-making process, even though he was very much a part of that machinery that made that decision. So it was, in some ways, a breaking point for him.

Ben: The book covers these just incredibly destabilizing layoffs. I remember the time people were saying, “I don’t know if they’re gonna be able to keep the website online.” I still use Twitter. It seems like it works OK. Was Musk basically right, that they were wildly overstaffed?

Kate: So that is actually something that the company had believed previously. Under Parag Agrawal, there were plans for mass layoffs that got put on hold when Elon came in and made the offer to buy the company. But it was something that I think that both management[s] agreed on, that the company was overstaffed.

That being said, I think that Elon’s cuts, by any measure, are quite severe, and the site still functions well enough to get by, but I think there’s a lot of things in the overall stability that are broken. You know, there’s some outages — yesterday, for example, timelines weren’t loading out here on the West Coast; a lot of search functions are broken now. You can’t really dig as easily into the archive of Twitter and see what people have posted in the past. There’s no longer any transparency reporting their advertising. And there’s no longer a robust sales apparatus to keep that business afloat. And so the core product, I think, is still chugging along, but there are a lot of things along the periphery that are broken and are not functional at this point.

Ryan: When we were reporting, someone told us this great metaphor of, “Twitter’s a pretty well-run car. Think about a car. And, you know, as you start to swap out parts, maybe it continues to run and run and run and run, but eventually it’s going to hit problems as you continue to take out parts.” And that stuck with me for a while. I think there’s always going to be people that use Twitter, but I think it’s pretty undeniable that he has made it a worse experience.

Ben: How much of Musk’s own identity and way of being in the world now a product of spending a lot of time on Twitter?

Ryan: I think a lot. If you go back and look at his early tweets, it’s very funny, because he really didn’t like the medium. His earliest tweets were like, hanging out with his kids at the ice rink and photos of Kanye West wearing SpaceX, pretty normie stuff. It was just online for everyone to see.

But then he starts to grasp, “this is an outlet for me.” Like he starts tweeting about book recommendations and his thoughts on SpaceX. And then I think there’s a lightbulb moment that clicks for him, where he uses this thing to push back on any media narrative.

Even early Elon hated the media, he loved fighting and debating and pushing back on anything that was wrong. There were tweets about him fighting over a detail in a reporter’s story about what he ate for breakfast and that just became part of what he did every day — so much so that we talked to Twitter or to former staffers of his that were told to go fight, like, some random blogger in Belgium over tweets. He would stay up till 3 a.m. telling his communications staffers to do this. And so that happened over the last decade, where he grew to mistrust media, learned how to use Twitter effectively for his own message, built a following and just spent hours every day on there, to the point where it became his main social circle.

Ben: How does your understanding of Musk from what’s basically like a disaster movie of a book fit into this person who’s undeniably accomplished, in a business context — built some stuff that is quite amazing and transformative.

Ryan: He contains multitudes! That’s a cliche. Just because you’re a successful entrepreneur in rocketry or electrifying vehicles, doesn’t necessarily make you the best person to run a social media network.

Kate: I think X/Twitter is a fundamentally human problem. It’s a social problem. It’s less of an engineering feat. And where Musk has really shown [strength] in the past is in engineering and hardware, and that’s just not a problem that Twitter addresses.

Reed Albergotti: Was Elon surprised that advertisers fled? Did that catch him off-guard? Or was he always kind of like, “Oh, screw it, I don’t need these people, I’m gonna just stop my mouth off.” And do you think that he can potentially, one day get advertisers back to Twitter? Or has that ship completely sailed?

Ryan: I don’t think he had a plan, really. All our reporting shows that there wasn’t much thought into this, and he was really leaning heavily — a lot of his focus was on Twitter Blue, building the subscription model, really believing that he could sell this to millions of people. And it wasn’t till he walked through the doors, like after the sink moment, that I think he started talking with some executives and realizing there are concerns about his tweets and his ownership, and that we really do have to woo advertisers.

So there was that brief period where he wrote a note, it was a pretty well-written note, to advertisers, trying to assuage them and comfort them in a way. But like everything with Elon, he can whiplash back and forth and throw a lot of good work out the window. There’s one moment we have in the book where he’s in a meeting with a top ad executive, and the ad executive asks him, “is Donald Trump going to be back on the platform?” And in response, he whips up a tweet and he says, “if I had a nickel for every time someone asked me if Donald Trump would be on the platform, I’d be a rich person.” And he shows it to the ad executive and asks him, “Should I tweet this?” It’s such an insane moment. This isn’t just like normal behavior, but there’s no one really holding him accountable to this. And he just kind of does what he wants.

Kate: Something that we encountered time and time again in reporting this book is that Elon cannot handle public criticism very well if he needs to be corrected. That has to be done in private and when he’s confronted publicly, he will react very aggressively and kind of double down, and we’ve seen that in his relationship with advertisers. When there’s been publicity around advertisers pausing their campaigns on the platform, he’s reacted very negatively to that. And I don’t think that there is a world where a lot of mainstream advertisers return and are the fundamental part of Twitter’s business that they used to be.

Ben: What did you wind up thinking about Walter Isaacson’s biography?

Kate: I was worried about that book. We knew it was going to come out before ours. And I was worried, are we going to get scooped on all this stuff that we knew he was in the room for? And I think we got really lucky, in that his focus and his sourcing was really spotlighted on Elon himself. We had really the privilege of reporting around Elon and working with a lot of sources who were in his periphery. And I think that really benefited us.

I think we all know this in journalism, that people are unreliable narrators of their own stories, and it can be really helpful to talk to folks around them to get a fuller picture. And I think Elon is a great example of that, and someone who’s very unreliable about his own story, and that it is really a benefit to go to the people around him to get the truest picture of him. And I think in that circumstance, our sourcing just really benefited us to obviously not have access to Elon, and have access to the folks around him.

Ryan: In some ways, we treated that book like the voice of Elon. We use it in our sourcing material. We mentioned it. Let’s say some event happens, then Elon will spout off on it, and then Walter just writes about it. And it’s great to understand Elon’s thought process at the time, as well as where he was. There’s a lot of physical detail in there that helped us a lot in placing him. But as soon as we started to talk to folks, maybe one level down from executives, we started to realize Walter didn’t really talk with them at all. There wasn’t much beneath the surface reporting and beyond that. He had kind of become captured by Elon in some ways, he became an adviser.