The News

Three countries in Central Africa’s Congo Basin are being closely watched for the possibility of a future political upheaval or coups after the fall of the Bongo dynasty in neighboring Gabon.

Cameroon, Congo Brazzaville, and Equatorial Guinea are seen by analysts and long-time Africa watchers as having similar conditions of decades-long rulers, multigenerational economic mismanagement, and an agitated, resentful populace.

There have been eight coups in West and Central Africa since 2020 and there are concerns in the international community that there is a high risk of contagion in these regions.

In this article:

Know More

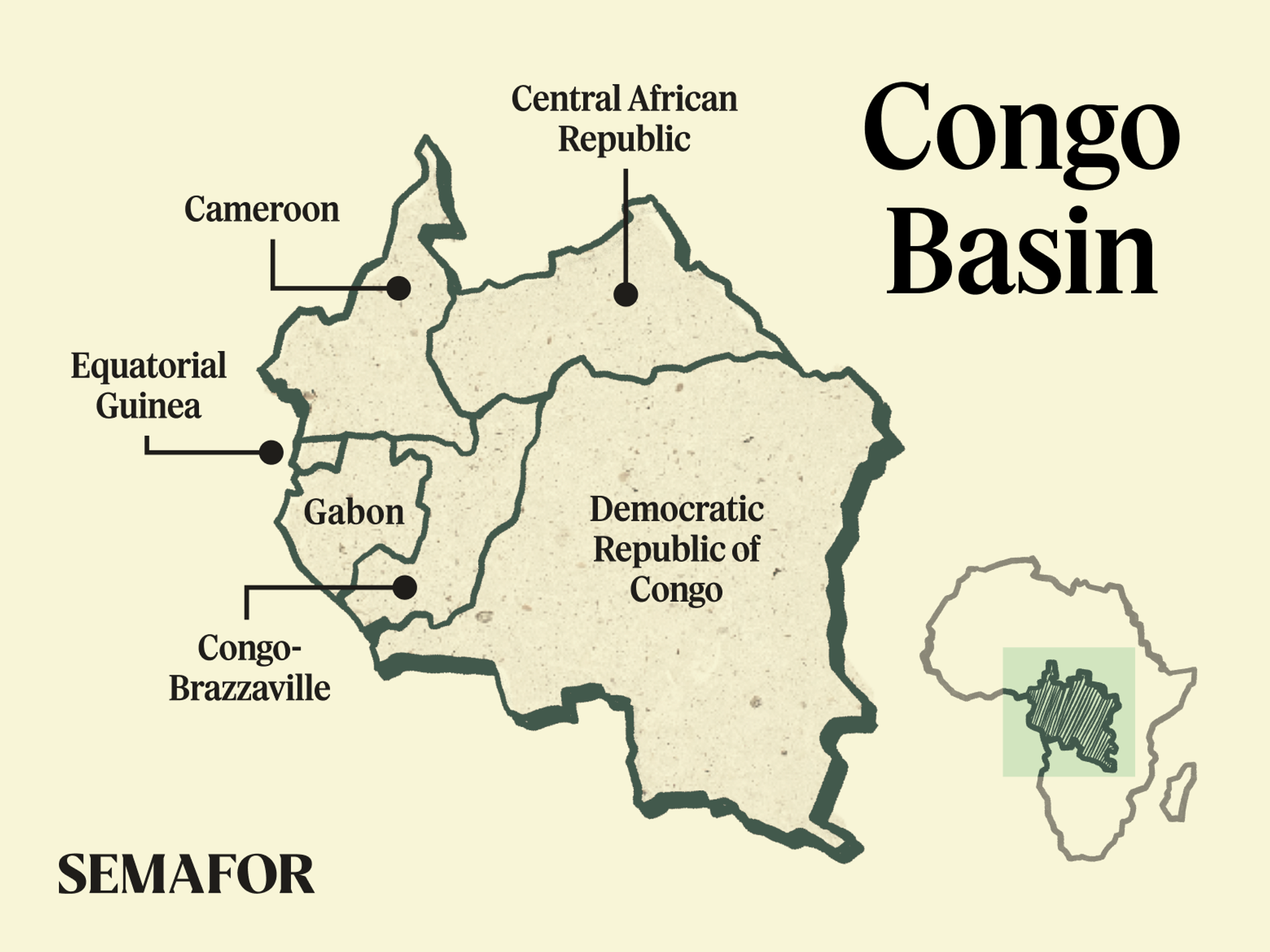

The Congo Basin, best known for rainforests that absorb more carbon than the Amazon, spans six countries: Cameroon, Central African Republic, Congo Brazzaville, Democratic Republic of Congo, Equatorial Guinea and Gabon. It is home to some of the world’s longest-running authoritarian regimes but also hosts some very unstable political systems.

The vast majority of people born in Equatorial Guinea, Cameroon, and Congo Brazzaville have only ever known one leader. The political systems of the Central African Republic is undergoing upheaval while the uncertainty around DR Congo’s December elections weighs heavy on the country and its neighbors.

Like with the most recent West African coups in Burkina Faso, Guinea, Mali, and Niger, five of the six Congo Basin countries are Francophone. One of the common themes in West Africa has been strong anti-French populist rhetoric by the coup leaders.

Yinka’s view

Predicting where a coup will happen can be a fool’s errand at the best of times because there are too many variables to consider. But noting the conditions that encourage and enable them is a useful exercise because many of those factors apply equally in representative democracies.

The basic question citizens are asking is “what has my government done for me lately?” Survey after survey shows Africans broadly prefer democracy over military rule but if you’d seen the images of celebration of the coup out of Libreville, Gabon last month, you might think the opposite.

Georgetown University political scientist Ken Opalo said there’s a real risk of contagion in the region, especially with long-serving ineffective leaders. “The elevated coup risk in many countries is not necessarily about civilian tolerance of coups — big majorities abhor military rule — but about the failure of civilian rule over the last three decades,” he told me.

It’s worth noting that while surveys often show a preference for democracy in Africa, surveys by polling company Afrobarometer have also shown a high institutional trust in the military in many countries, sometimes higher than local judiciaries. “The military are seeing those numbers too,” noted W. Gyude Moore, a senior fellow at the Center for Global Development. “So in countries where you have used the security services to keep yourself in power then they (the military) soon understand that they are in fact the ones with the power.”

A case in point was in Gabon where the deposed Ali Bongo, in a widely circulated video, called for the international community and Gabonese people to “make noise” on his behalf. “All of the democratic institutions, political parties, civil society, or media that would defend the constitutional order, had all been systematically undermined by the use of force,” said Moore, who was previously a government minister in Liberia. “The military knows that in all of these cases there is going to be no resistance.”

Well, there is some resistance but most of that has come from France as the loudest critic of the recent trend of coups all of which have happened in its former colonies. There is even an ongoing behind-the-scenes dispute over the aftermath of the Niger coup with the United States, which appears to have taken a more pragmatic approach in response. The French influence interests here run deep, said several of the analysts we spoke with.

“The two countries to watch are Congo Brazzaville and Cameroon,” said Mvemba Dizolele, director of the Africa program at the Washington based Center for Strategic and International Studies. “These are two countries where the French currently have a strong grip, they both have aged leaders who have mismanaged their countries.”

But there’s also a possibility that the French may turn a blind eye to future coup plotters if the governments are unpopular and there are assurances France’s interests will be protected. The Gabon coup is already being framed that way.

That might explain why Cameroon’s President Paul Biya recently reshuffled his top military brass. In Brazzaville, President Denis Sassou Nguesso had a reshuffle back in January but some say family disputes around the 79-year old could provide an opportunity for someone to make a move, including his nephew and intelligence chief Jean-Dominique Okemba. “There are a lot of people there with their own ambitions and their own relationships to France,” explained CSIS’s Dizolele.

Notable

- Why the Gabon coup and downfall of the Bongo dynasty was so different from the recent coups in West Africa. Semafor’s Alexander Onukwue explains.