One Big Idea

Wael Mahdi is an independent commentator specializing in OPEC and Saudi Arabia’s economy, and co-author of “OPEC in a Shale Oil World: Where to Next?”

During my 15 years covering OPEC, I was hounded by traders, policymakers, and my editors with the same question: Will it cut, boost, or keep supplies steady? With a decision looming in December, I know you are expecting a forecast.

The truth is, it’s a coin toss, with too many factors at play to make a prediction, at least not yet. But a deeper, more existential, question looms. And one person is better placed to answer than most.

So last Wednesday, I went to visit Hassan Yassin for dinner at his home in Riyadh. Now 91, he was one of the first employees of Saudi Arabia’s Ministry of Petroleum and, in 1959, worked closely with the kingdom’s first Oil Minister Abdallah Al-Tariki, one of OPEC’s founding fathers.

During dinner — beef and vegetable stew — as he was sharing stories of OPEC’s early days, his nephew asked the question on many of our minds: Is OPEC over?

The core question now is whether the 64-year-old institution can maintain unity, and for how long: OPEC, which played a key role in stabilizing global energy markets in recent years — especially during the pandemic — is under pressure. Members are boosting capacity even as the group limits supply. Tens of billions of dollars in investments sit idle. Renewable energy is gaining market share.

In this context, the slack demand in China and stock buildups elsewhere which are captivating markets are fleeting issues.

There are five major challenges that will determine whether OPEC is relevant for decades to come.

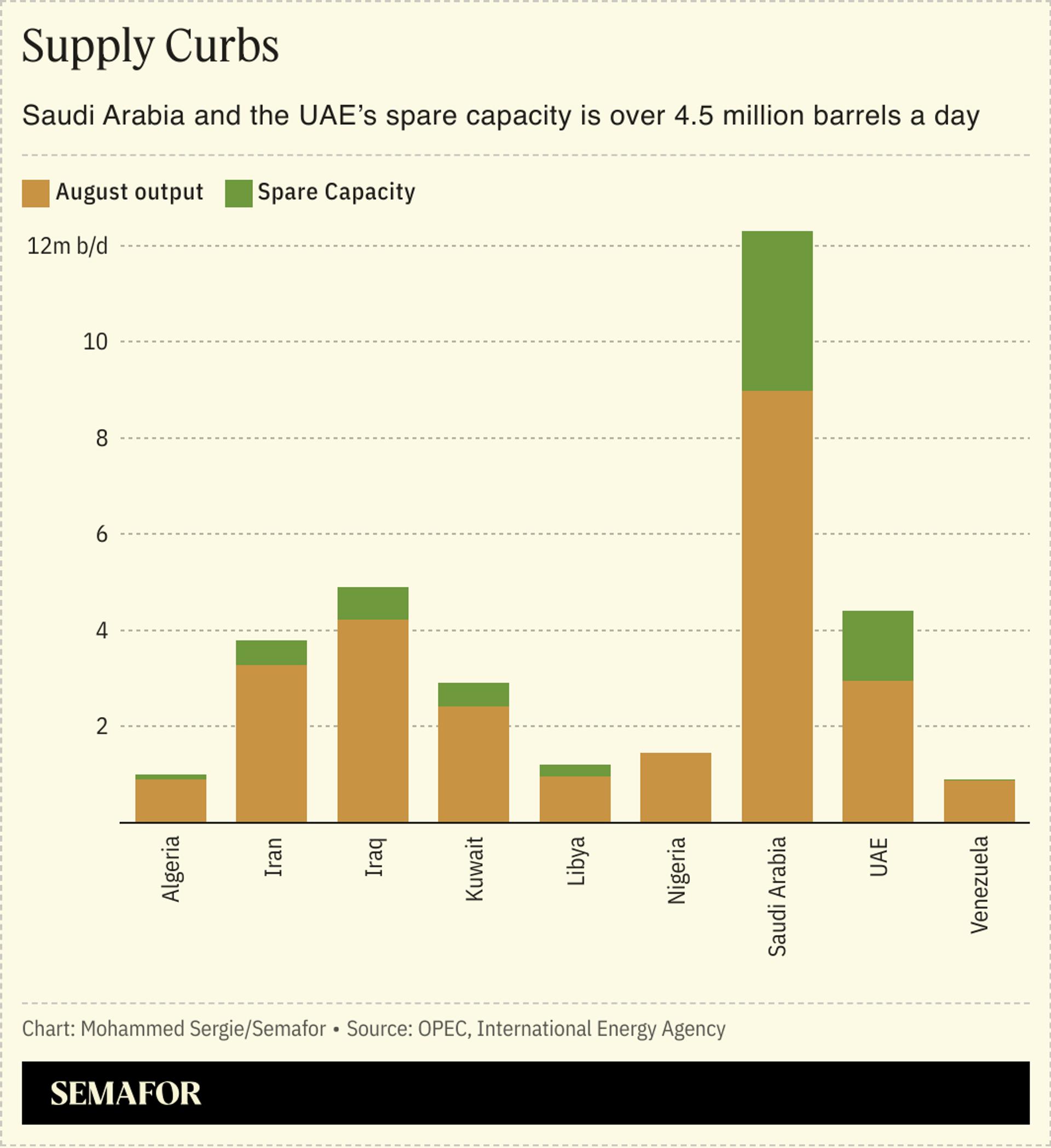

- Rising Capacity: Iraq and the UAE are ramping up capacity, the former to 7 million barrels a day and the latter to 5 million a day by 2027. Both countries are currently producing a combined 7 million barrels per day under the OPEC+ voluntary cuts, which apply at least until December. Add in the sanctions constraining Iran and OPEC’s partner, Russia, and there’s a deluge waiting on the sidelines. The group must strike a balance that allows members to benefit from these investments while keeping the market stable. Non-compliance — or more bluntly, cheating — could become rampant, eroding the group’s cohesion and effectiveness.

- US Dilemma: OPEC doesn’t sell much oil to the US, the world’s biggest producer, and Washington generally favors lower prices, even if it hurts its own domestic shale sector. The group needs to build better relations with the US, which is often hostile to the organization and periodically threatens to enact the NOPEC (No Oil Producing and Exporting Cartels) bill — which would allow the US attorney general to sue OPEC and its members for antitrust violation. From November, OPEC will need to manage a new president and his or her views on the organization.

- OPEC+ Sunset: OPEC expanded in 2016, working with Russia and nine other producers. This alliance, however, doesn’t share OPEC’s formal structure and could be dissolved at any moment depending on the direction of oil prices, a fracture that would weaken OPEC’s influence.

- Petro-Dollar: China and India are crucial OPEC customers. Beijing has been adamant about using its yuan currency for purchases, with limited success. Oil producers have benefited from, and prefer, the more stable dollar. If some sellers decide to placate buyers and shift from the dollar, their decision could lead to fissures and complicate OPEC’s core goal of keeping future oil prices stable.

- Unity: The group’s unity has always been fragile. Several countries have left the organization in the past, including Angola, Ecuador, Gabon, Indonesia, and Qatar (though Gabon later rejoined). These exits often stemmed from disagreements over quotas or a desire for more independent energy policies. Smaller members have little say, making it increasingly difficult to keep the group together as interests diverge.

During dinner, Yassin — unsurprisingly — argued that OPEC was still relevant, “because the world needs stable oil prices.”

Yet as he recounted the early days of the group — a thrilling history that includes global price wars and hijacked planes involving Carlos the Jackal — the tales felt disconnected from the challenges OPEC faces today.

These challenges aren’t insurmountable, but the odds are stacked against OPEC. It could easily fade into history, a notion Yassin can’t fathom. Many others — his own nephew included — believe that change may be inevitable.