The News

At the U.N.’s Climate Ambition Summit yesterday, ambition was in short supply.

Brazil reinstated a stricter emissions target that had been scrapped under former President Jair Bolsonaro. A few European countries tossed out relatively meager new contributions to the Green Climate Fund. But apart from that, the succession of speeches by world leaders throughout the morning mostly retrod well-worn ground.

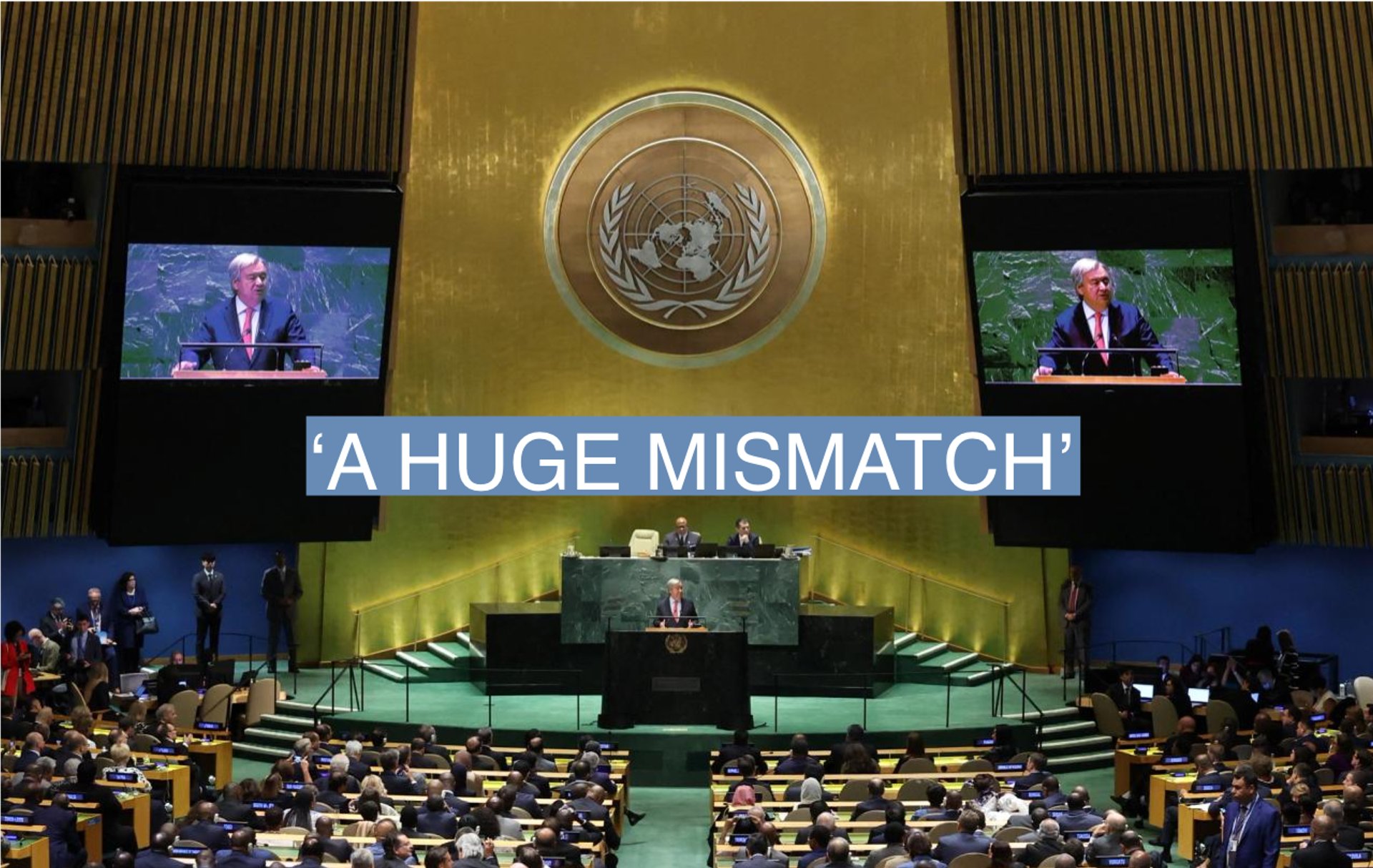

“The small steps countries offered are welcome, but they’re like trying to put out an inferno with a leaking hose,” David Waskow, director of the International Climate Initiative at the World Resources Institute, said. “There is simply a huge mismatch between the depth of actions governments and businesses are taking and the transformative shifts that are needed to address the climate crisis.”

Tim’s view

The lackluster outcome raises the stakes for COP28 to produce more meaningful policy changes, but also underscores both how unlikely that is and the severe limitations of the U.N. itself in driving the necessary shift. The 2015 Paris Agreement was a high point for climate diplomacy, but since then, countries have found it much easier to agree on what needs to be done than to actually do it.

In his opening statement, U.N. Secretary-General Antonio Guterres complained that “shady pledges have betrayed the public trust,” and blamed “foot-dragging, arm-twisting, and the naked greed of entrenched interests raking in billions from fossil fuels” for the lack of decisive action.

In organizing the summit, Guterres chose a novel tactic, handing the microphone only to leaders his office deemed to have taken sufficient domestic action. That left out many of the world’s top emitters, including the U.S., China, India, and COP28 host the United Arab Emirates. The move was designed to create a kind of coalition of the willing and more clearly delineate leaders from laggards. But it risks splintering the delicate multilateral coalitions that typically drive the biggest COP outcomes, said Tom Evans, policy adviser at the think tank E3G. And in any case even the countries that were allowed to speak have for the most part not done nearly enough, as the U.N.’s global stocktake report this month made clear.

There was also no progress Wednesday on the issue that will be most contentious at COP28: A commitment to phase out the use of fossil fuels. The UAE is against such a goal, the COP28 director-general told me this week.

“They’re saying lots of good things about the agenda but not showcasing their own leadership or putting their money where their mouth is,” Evans said.

Quotable

“If you don’t take corrective action, you’ll have to tell us where you’re keeping your scientific research that will allow you to take you and your families to the planet Mars.” — Barbados Prime Minister Mia Mottley in her address to the U.N., speaking of oil and gas company executives.

The View From BRICS

There were some modest signs of progress on the issue of climate reparations payments for the most-impacted low-income countries. Leaders agreed at COP27 last year to set up a loss and damage fund, but it’s still unclear how it will be resourced. In a session led by Rachel Kyte, dean emerita of the Tufts University graduate school for international affairs, representatives of a number of multilateral development banks laid out suggestions, including the introduction of low-cost disaster insurance and the repurposing of some existing aid finance.

“There was incremental progress today and more collaboration than we have seen before but this is not a moment for an incremental response,” Kyte said in an email afterwards. “We need a step change.”

And there’s a chance that the fund could be derailed by a disagreement among rich countries about who exactly it should target, according to a Western official on the loss and damage committee who asked to remain anonymous to discuss private negotiations. Some are pushing for it to be accessible only to the least-developed countries and island nations, while many middle-income countries, including those like South Africa and India in the BRICS group, are insisting they too should qualify. So there’s a strong possibility that the negotiations that took place over the last year will have to be scrapped and restarted at COP28, the official said.

Room for Disagreement

The biggest round of applause during the summit went to California Governor Gavin Newsom, when he said that “this climate crisis is a fossil fuel crisis.” Newsom, whose state recently adopted some of the world’s toughest corporate climate disclosure rules and is suing a group of oil majors for misleading the public about climate science, was one of a handful of sub-national leaders to speak, including London Mayor Sadiq Khan. In past summits, state and local leaders have often been more proactive than national ones, and that seems likely to continue.

Notable

- The summit offered another turn in the spotlight for Kenyan President William Ruto, fresh off of hosting the Africa Climate Summit in Nairobi earlier this month. Ruto was the first to speak, and said that “Africa does not need handouts — what we need is fairness.”