The 1970s oil shocks — driven in large part by Gulf policies — deeply scarred the US, providing the impetus for bets on nascent drilling technologies that took decades to bear fruit, but which inoculated the US from a repeat crisis, and ultimately turned it into the world’s biggest oil producer.

Ironically, the success of those investments have now driven several countries in the Gulf to themselves take radical steps to shift from the myopic economic policies of yesteryear, and cut their own dependence on oil.

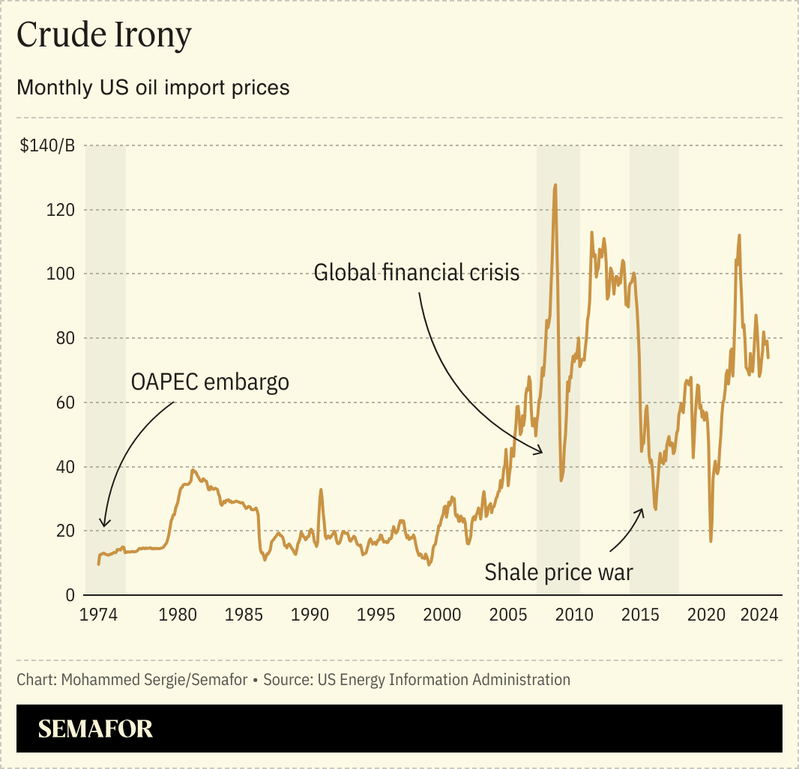

In 1973, following the outbreak of the Yom Kippur War, the Organization of Arab Oil Exporting Countries (OAPEC) slashed oil production as a way of exerting pressure on Washington and other governments perceived to be supporting Israel. The result was a quadrupling of oil prices, inducing an economic crisis in the US. The embargo was lifted the following year, but it would have profound consequences that extended well into the 21st century.

The idea of using trade embargoes as a coercive tool in international relations has a long history. One of the most famous examples was Napoleon’s efforts against the British during the early 19th century, as he tried to starve France’s long-standing nemesis. To this day, Cubans live under a US embargo imposed following the country’s Communist revolution.

What was unusual about OAPEC flexing its muscles, however, was that it represented a rare example of economically and politically marginal countries trying to squeeze global superpowers. This act of defiance did not sit well with countries that were used to dictating terms to the rest of the world. Thus, even if the economic damage was limited and transient, decisive actions that would prevent a recurrence had to be taken, even if only to protect the prestige of the world’s most powerful nations.

In the US, a key development was the institutionalization of efforts at developing alternative energy sources, most notably shale oil. While the geological principle of extracting oil from shale deposits was well-established before the 1970s, it wasn’t commercially viable. The embargo led to the US allocating huge resources to research in this area. Around 30 years later, shale oil extraction became profitable, with significant expansion in production occurring during the Obama presidency, leading to a sharp decline in US reliance on Middle East oil, a not-insignificant development laying the groundwork for the 2011 announcement of the “pivot to Asia.”

The near doubling of US crude oil production to 9.5 million barrels per day from 2010 to 2015 rocked global oil markets. Oil prices were around $140 a barrel in mid-2014, but the surge in supply caused prices to crash to $40. For the Gulf countries, this was an unmitigated disaster, as so much of their economy — and with it their sociopolitical system — depended on high and stable oil prices.

While several Gulf countries launched economic reform plans well before that crash, for the biggest and most important regional economy — Saudi Arabia — the crisis provided the impetus for building a totally different economy, coinciding with the passing of King Abdullah bin Abdulaziz and the transfer of power to his younger brother, King Salman. Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman became the standard bearer for Saudi Vision 2030, and during the eight years that have passed since its launch, Saudi society has undergone a profound transformation.

Some of the more obvious changes include the rapid transition from effectively zero non-religious tourism to allowing visitors to secure electronic visas and explore everything from boxing matches to yoga retreats. Women’s labor force participation has surged, while the kingdom has expanded manufacturing into new sectors such as arms and electric vehicles. Notably, in a manner that harks back to the US’ own commitment to alternative energy in the 1970s, the Gulf countries have been investing heavily in solar, wind, hydrogen, and other forms of clean power as a hedge against a future oil price crash.

Critically, the transformation inherent in Saudi Vision 2030 closes the door on the previous structure of the economy. A similar push has occurred in Bahrain, Oman, and the UAE, all of whom realize that this might be their last chance to reform their economies from a position of strength. Through wholesale changes in personnel and mindset, the government bureaucracy in the Gulf states is now dominated by people who firmly believe that diversifying the economy is an act of national self-preservation.

This institutionalization contrasts with half-hearted diversification attempts following the 1980s crash in commodity prices. At that time, the economic pressure was lower, and there was a belief among policymakers in the Gulf that they were at the nadir in a cycle, meaning that they just had to wait for the good times to come back, which they did.

The party did eventually stop, though — and all thanks to the shale oil revolution that the Gulf countries inadvertently brought about via the 1970s oil embargo, in a manner that mimics the Lion King’s “Circle of Life.”

Just as the psychological and economic pain that the US experienced convinced it to institute permanent reforms, so too did the analogous pain that the Gulf states felt in 2014-2016. The region will be hoping that the symmetry of its efforts to those of the US yields symmetry in outcomes, too.

Omar Al-Ubaydli (@omareconomics) is the Director of Research at the Bahrain Center for Strategic, International and Energy Studies (Derasat), and a contributor to Semafor.