The Scene

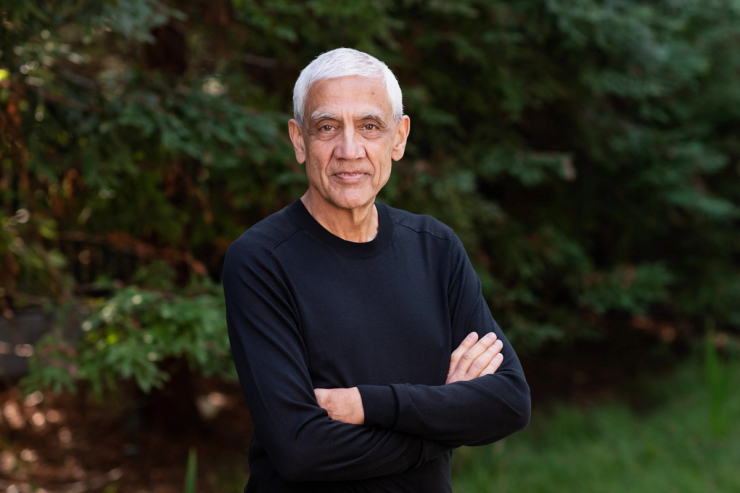

Vinod Khosla, the entrepreneur-turned-investor, has had an outsized impact on the development of modern day Silicon Valley. He pioneered the idea of open-source software as co-founder of Sun Microsystems and then, as a venture capitalist, helped fund the next generation of companies that pushed the boundaries of robotics, artificial intelligence, and clean tech.

Khosla explained in a recent paper why he believes the next wave of technology — driven by generative AI — may have the biggest impact on humanity yet. It’s no secret that Khosla, an early investor in OpenAI, is a huge proponent of AI, but the Sept. 20 paper is a detailed treatise on why the naysayers (the Screen Actors Guild, politicians, etc.) and global challenges (conflict and supply-chain breakdowns) are standing in the way of a potential utopia.

In a wide-ranging interview, Khosla addressed some of the big, overarching questions facing AI today, including the monumental challenge of generating enough clean energy, the opportunities and challenges presented by the Gulf states, and the drama at OpenAI.

Q&A

Reed Albergotti: These AI models are getting so big; people are talking about five gigawatt data centers. It seems beyond the scale of the private sector at some point. How do you see the public sector coming in here?

Vinod Khosla: It’s very hard to decide today. Obviously, the dollars are getting large and the projections are getting large. It depends on the model size. The models are becoming bigger and bigger. But how much compute they take to do an inference, to write a piece for you, is becoming more efficient. If it cost $15 for 1 million tokens 18 months ago, it’s 15 cents today. How far it goes is very hard to predict.

I’m optimistic that other techniques will come in, and people are working on so many different approaches.

One big area where there’s probably large disagreement on how the models work is robotics. It’s sometimes called embodied intelligence. Is it the same model? Is it a different model? We don’t know a lot about this.

You have to plan in advance, because data centers take five years to build, and power plants can take even longer.

There is a lot of risk being taken, which is best done by capitalists, not by government[s]. They’re just too slow to do this. Also, governments can’t hire the quality of people needed. There’s engineers, three years out of PhD, making $1 million dollars or more. I’ve seen some ridiculous numbers, even higher. They can’t hire these people.

So when people say governments should regulate, they don’t have the people who can keep up. They aren’t as dynamic, and you can’t change policy every six months or 12 months. But our plans change every six months. It’s a very dynamic situation, and we just have to go with the flow and place our bets. Government can’t do that. It can’t hire the people. It can’t pay ridiculous salaries.

Reed: If you’re building five or six data centers, and each one is five gigawatts of power, I don’t see how that’s entirely done by the private sector because there isn’t enough power right now.

Vinod: The question you should ask is, is there enough capital, not if there’s enough power. Because if there’s enough capital, people will do all kinds of clever things. Government would not have imagined the Three Mile Island nuclear power plant can be put back in production. Definitely not without five years of debate. So private companies move quickly. The capital moves quickly. In fact, too quickly, sometimes.

You can deploy a gigawatt of solar pretty easily now, and you can put a data center wherever you want. So all sorts of bets are being placed. I think fusion is coming, and there’s people willing to bet that in the early 2030s they’ll be building gigawatt data centers from fusion. If the government listens to experts, they’ll say it’s not possible.

We invested in OpenAI and Commonwealth Fusion, and, by the way, a public transit system, in 2018 and 2019. People said for all three, this is totally ridiculous and irresponsible investing. All three look like awesome bets today.

Reed: I met with some people in the UAE a few weeks ago and wrote about how the US is now allowing Nvidia to sell its most advanced chips over there. But there are US national security folks who say we shouldn’t trust them because of links to China. How do you feel about that?

Vinod: We can’t just not trust anybody, but we should be careful. State-of-the-art training is something we should hold close to the chest, and I’ve gone on the record saying we shouldn’t allow open sourcing of state-of-the-art models, but only state-of-the-art models. That applies to China but also to the Mideast. But I think there’s lots of room, and the Middle East is a complex place. Even in the Mideast, the Kuwaitis, the Emiratis, the Saudis, the Iranians, they’re not friends with each other. There’s a complex game theory dynamic there that I don’t understand. Putting a data center there is probably fine. Sending technology there that’s in development would probably not be appropriate for [US] national security reasons.

Reed: It sounds a bit like Taiwan, when the chip companies said, ‘We’ll allow the fabs to be built in Taiwan or Korea or wherever, but we will keep the IP. We won’t send the blueprints.’ Are there any similarities?

Vinod: There are a lot of similarities. I think the situation in chips is a little different. And again, I’m going to go into speculation that I don’t fully understand. [Taiwan Semiconductor] started in Taiwan, so we didn’t have a choice. They beat out Western sources of process technology. Making sure we are not dependent on just Taiwan is absolutely critical from a [US] national security point of view, hence the CHIPS Act.

Reed: It sounds like you think that having a giant data center that’s capable of training a state-of-the-art foundation model doesn’t necessarily mean they would somehow be able to glean valuable IP.

Vinod: Well, the thing with these complex models is it’s hard to say what can be gotten from what. OpenAI has this new reasoning model, which is a quantum jump in reasoning capability of these models. [It] essentially says you can’t ask it ‘How did you arrive at that conclusion?’ because in that answer maybe hints about the technology.

This is why it’s too complex to really easily explain. Some of these models can be reverse engineered. Others can’t. So we just have to be cautious.

Reed: You talked about solar and fusion. Is it possible to build these data centers without emitting more greenhouse gasses?

Vinod: I don’t think these will scale up with fossil technology. You can’t permit a coal plant or a natural gas plant quick enough, especially with permitting cycles and controversies and lawsuits and all that. Solar is very, very scalable. Storage, not quite so. My favorite is super hot geothermal, followed by fusion.

Reed: In other words, you might need a supplement. You build a gigawatt of solar, but at night, you have to use some fossil fuels or traditional grid energy?

Vinos: Which is when there’s very little demand for traditional grid energy and power prices go negative. If you are using them at night, and the economics get better for solar or for traditional grid, we’ll see more investment in power. Look, none of these are easy problems. I’m not saying they’re trivial to solve, but I think people are paying attention to the right things. And when we do pay attention to the right things, things do get solved.

Reed: Brad Smith from Microsoft mentioned modular nuclear at our event last week, saying it was a technology for the 2030s. You didn’t mention that.

Vinod: I’m less bullish on that. I’m a real fan of nuclear. We invested in TerraPower. My worry is, because of NIMBYism, it’ll take longer to permit one nuclear power plant — 10 to 15 years after you’re done with all the lawsuits and NIMBYism — than it takes to build fusion reactors. I think that’s where I might disagree with Brad.

Reed: Your view seems to be very US-centric. What happens if other countries, perhaps Saudi Arabia, say, ‘we’ll just burn oil’?

Vinod: All these are real questions with no easy answers, but I do think we are moving in the right direction. We have enough focus on the right solutions. We’ve talked about renewable or not, but we also have to say, are they economic or not? The economics have to work too, from a pragmatic point of view.

Reed: You’re one of the first investors in OpenAI and you’re close with Sam Altman. All his top people have left. Are you concerned about the leadership at OpenAI?

Vinod: I’d say there’s so much demand, and the funding round is so oversubscribed. That should tell you — not to say I didn’t get calls from people.

Reed: The Information reported that there was some investor who was very concerned about the leadership at OpenAI.

Vinod: I don’t know who they talk to. They haven’t talked to me.

Reed: The other concern is that they’ve lost so much talent that they’re going to lose their secret sauce, essentially.

Vinod: I don’t believe so. I think they have a pretty good depth of talent. Look, if you just Google the people who’ve left DeepMind, it’s probably a far greater number.

Reed: People like Jakub Pachocki are stepping in to replace Ilya Sutskever? Was he on the rise already?

Vinod: He was definitely on the rise.

Reed: What do you think of this narrative that people want to build around OpenAI and Sam?

Vinod: I think the problem here is reporters need column inches to fill. It’s all about clickbait. It’s not about reporting.

Reed: Did you see this switch from the non-profit structure to the for-profit structure coming, as an investor?

Vinod: Look, it works the current way. It’s more constrained, and nobody anticipated needing money at this scale, in which case you have to have access to traditional markets. And nobody anticipated this massive revenue. I won’t go into the revenue, but it’s a pretty damn amazing revenue ramp. Never-been-done-in-history kind of numbers.