The Scene

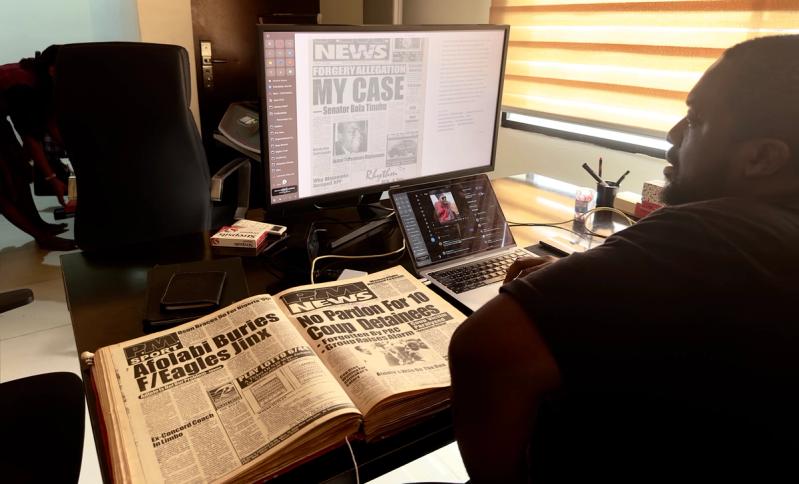

LAGOS — The office where Fu’ad Lawal and his team of four work out of is an intentionally dimly-lit upstairs bedroom in his home, somewhere in the Lekki neighborhood of Lagos. On their best day, they scanned 900 pages of newspapers published sometime in the last thirty years. They have uploaded 50,000 pages to their website Archivi.ng, but it is only a small step of a grand ambition.

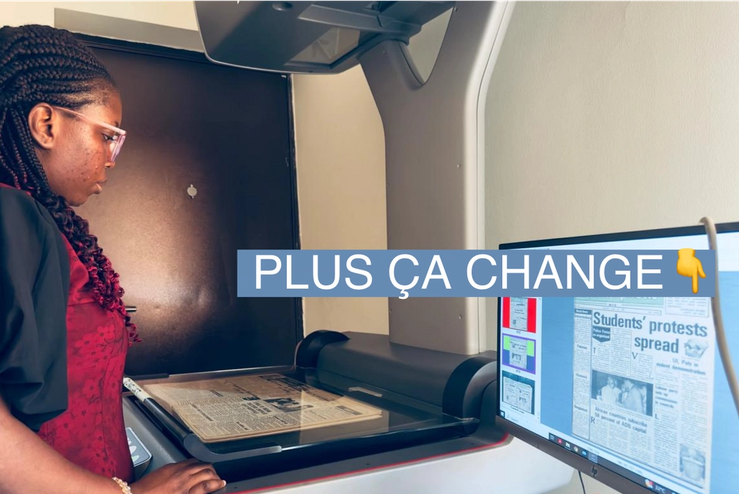

Lawal’s goal with Archivi.ng is to digitize every Nigerian newspaper published every day since independence in 1960. It is a history project to provide context for conversations about politics and the economy but also a record of language, culture and mundane aspects of Nigerian life, he says. It formally started in April when the team procured a seven-feet tall overhead scanner after raising $15,000 from donors since 2020.

Only one now-defunct newspaper’s complete daily editions between 1994 and 2010 have been scanned in the months since. But some of the pages freely accessible on the website — including those featuring decades-old allegations that current president Bola Tinubu may have used forged academic documents for elections in the 1990s — have gone viral online since Archivi.ng went live this October.

In this article:

Know More

When complete, Archivi.ng would contain at least 5 million pages of old newspapers. It would take five years to reach that goal with one scanner and four people, Lawal estimates.

Due to its current structure as a non-profit, the team continues to raise money only through donors. Many of those have been individuals who became aware of the project on social media. Access to the site is currently free but there’s a future in which Archivi.ng begins to charge for advanced types of use, Lawal says.

Alexander’s view

At the moment, the best places to read old Nigerian newspapers are in the libraries of some of the country’s oldest and most reputable public universities in Ibadan, Zaria, and Nsukka. But even those do not offer comprehensive repositories; poor care has led to some records being lost, and publishers serving particular regions have limited reach in others. In any case, not everyone can get to a physical library.

Archivi.ng is changing that dynamic dramatically. With features like search by date and AI-generated page summaries, it offers anyone with a smartphone access to what, for many, seems a trove of previously unknown history. Nigeria’s public education policy in recent decades has de-emphasized teaching history in primary and secondary classrooms for fears over ethnic tensions about what and how to teach, particularly on hot-button subjects like the post-independence Biafra civil war between the Nigerian government and southeastern soldiers.

Those ethnicity and religion-charged questions of prejudice and bias that have hampered the formal teaching of Nigerian history also come into play when relying on the rough drafts of past journalists. Newspapers from pre-independence Nigeria were typically founded by the most influential founding political figures in each region, whether Nnamdi Azikiwe’s West African Pilot in the southeast or Obafemi Awolowo’s Nigerian Tribune in the southwest.

It is why Archivi.ng’s northstar is to have as many different newspapers as possible for various viewpoints, without applying filters for publishers’ possible misinformation or propagandist leanings. “Editorial judgment is expensive,” Lawal told Semafor Africa. “Deciding what to scan is an extra layer of decision making that will cost us thousands of hours.”

Hard as it may seem, Lawal’s motivation is anchored on emerging information technology trends that demonstrate the need for recorded African history on the internet if the continent is to be part of the global economy. “How represented is African data in large language models? If you ask ChatGPT a question about pre-internet Nigerian history, it’s hard to find anything correct because there’s not a lot to work with,” he said.

The View From an Archivist

Kọ́lá Túbọ̀sún, a Nigerian writer, linguist and archivist, says Archivi.ng brings to life an idea to solve complaints he has identified severally. “The record keeping we do in Nigeria has not inspired confidence that people will have access to history and important documents,” he told Semafor Africa.

Túbọ̀sún cautions that it will take “a lot of money” and institutional effort to achieve a fully digital archive of newspapers. It could be necessary to design a profit motive for publishers to allow access to their work, he says (Lawal told Semafor Africa he has not paid fees for any of the papers).

As to whether good intentions and expertise can be assumed of newspapers and journalists of Nigeria past, “we don’t know that and we should not assume that,” Túbọ̀sún says. “The only thing we know is that they published history’s first draft. Newspapers tell you what people thought at a certain time, not a full account of what happened.”