The News

Food shortages across Africa — already forecast to be bad — will get worse next year, one of the UN’s top officials for global food supply chains told Semafor.

Russia said on Saturday it had suspended its participation in a deal to ease grain shipments from Ukraine after what it said was a Ukrainian drone attack on its fleet in Crimea. The agreement, brokered by the UN and Turkey in July, had helped restore the supply of grains and fertilizers to import-dependent countries across the continent after the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February.

But even before Moscow’s announcement, the president of the UN’s International Fund for Agricultural Development told Semafor food shortages were expected to deepen in 2023.

“Certainly, next year is going to be worse,” said Alvaro Lario, whose agency invests in long-term global food supplies.

He said many smallholder farmers cannot afford to buy the inputs needed, such as seeds and fertilizer, which would likely result in next year’s harvest being even worse than this year.

Lario noted there had been an increase in grain supplies reaching African countries since the blockade deal but said it was a “short-term fix” that “doesn’t solve the overall underinvestment in food systems.”

Shortages caused by the war deepened existing supply chain problems caused by the global pandemic and climate change, said Lario, adding that extreme weather continued to make the situation worse.

Alexis’s view

The war in Ukraine is just the latest in a series of shocks that have hit African countries. The full impact of extreme weather conditions on growers and those transporting goods within countries is yet to be felt and the global supply of fertilizers has been interrupted too. So we’re likely to see the shortages continue to play out for months to come.

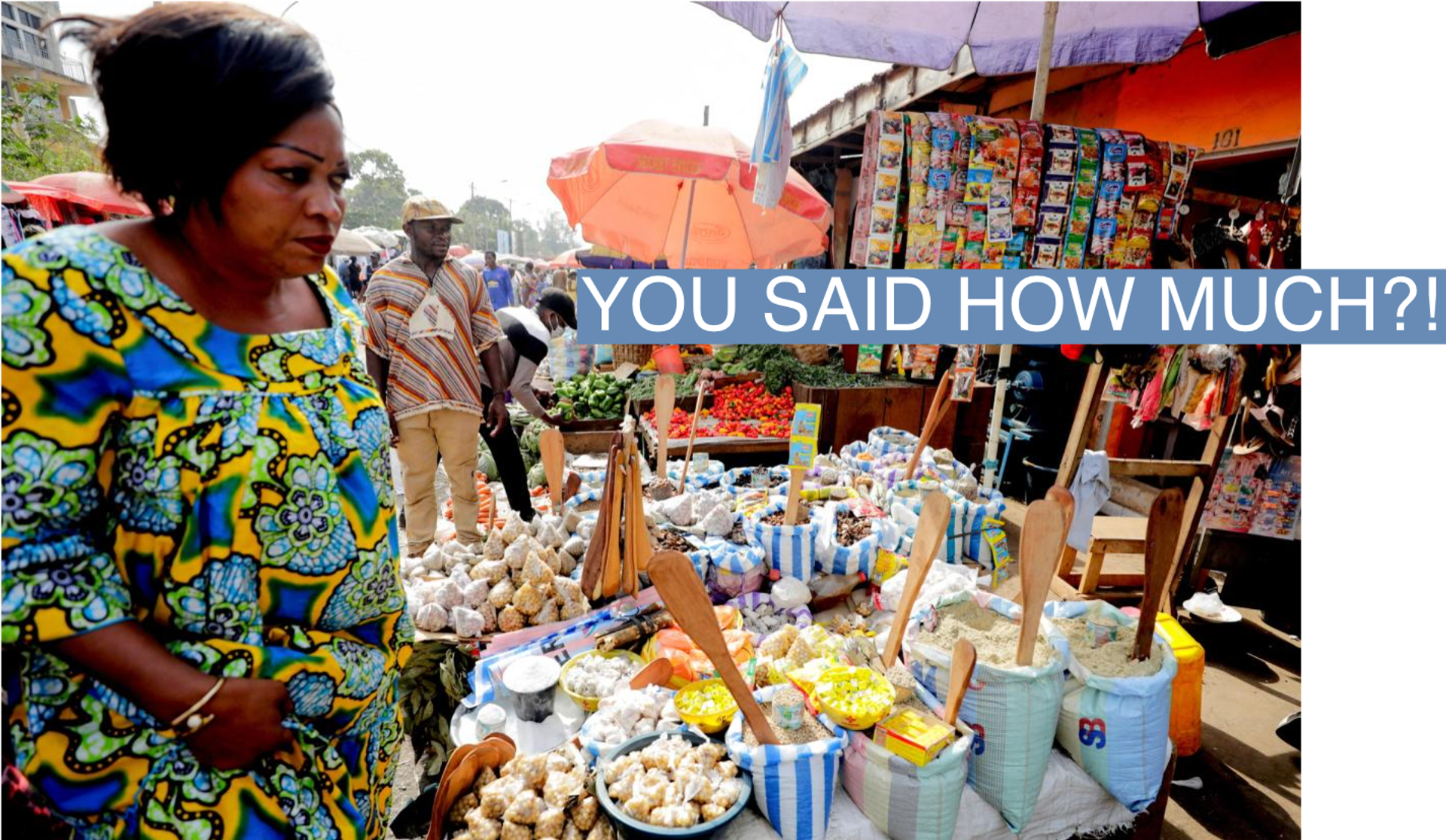

The shortages have driven galloping food inflation in many African countries, particularly those heavily reliant on imports. The IMF estimates that staple food prices in sub-Saharan Africa rose by an average of 23.9% between 2020 and 2022, the most since the 2008 global financial crisis.

Food shortages are significant beyond the obvious point that they drive up the cost of food that people need to live. They can stoke civil unrest and dictate the political mood.

The View From Kenya and Cameroon

Alice Mwikali Wambua, owner of a grocery store in the Kasarani neighborhood of Nairobi, said both she and her customers were struggling with high food prices. “We’re paying a premium to our suppliers and distributors to get our stock on the shelves,” she said. “I meet disconcerted customers who only make purchases because they cannot do without food.”

One of her customers, a teacher and father-of-four, said he was living “hand to mouth” as he struggled to cope with the rising prices. “I spend most of my earnings on food and household expenses, leaving very little to survive on,” he said.

Stephanie Noumbissi, a housewife in Cameroon’s capital city of Yaoundé, said she has been looking to buy a bottle of cooking oil for several days but the frequent price hikes have been extremely discouraging.

“Every day we wake up and discover that the prices of items like sugar, eggs, rice and other items have changed for the worse. How do you feed your family if you can’t get it? With the prices of some items now, it is hard to boast of three square meals a day.”

Room for Disagreement

The UN’s trade and development body, UNCTAD, said large shipments of grain are reaching world markets and “particularly to developing countries” due to increased port activity in Ukraine in recent months following the agreement reached to stop Black Sea blockades.

“The UN-led Initiative has helped to stabilize and subsequently lower global food prices and move precious grain from one of the world’s breadbaskets to the tables of those in need,” it said in a report published this month, before the latest news from Russia.

Notable

- High food prices and alleged impropriety in a fertilizer procurement deal prompted protesters in Malawi to take to the streets of Blantyre last week, reports Voice of America. It was just one of a number of demonstrations planned amid growing frustration over the rising cost of living.

- The Jollof Index, a food inflation report published quarterly by Nigerian political consultancy SBM Intelligence, calculated that the average cost of making a pot of jollof rice in Nigeria for a family of five increased from 9,220 naira in June to 9,917 naira in September - a 7.6% increase.

— With Muchira Gachenge in Nairobi and Beng Emmanuel Kum in Yaoundé