The Scoop

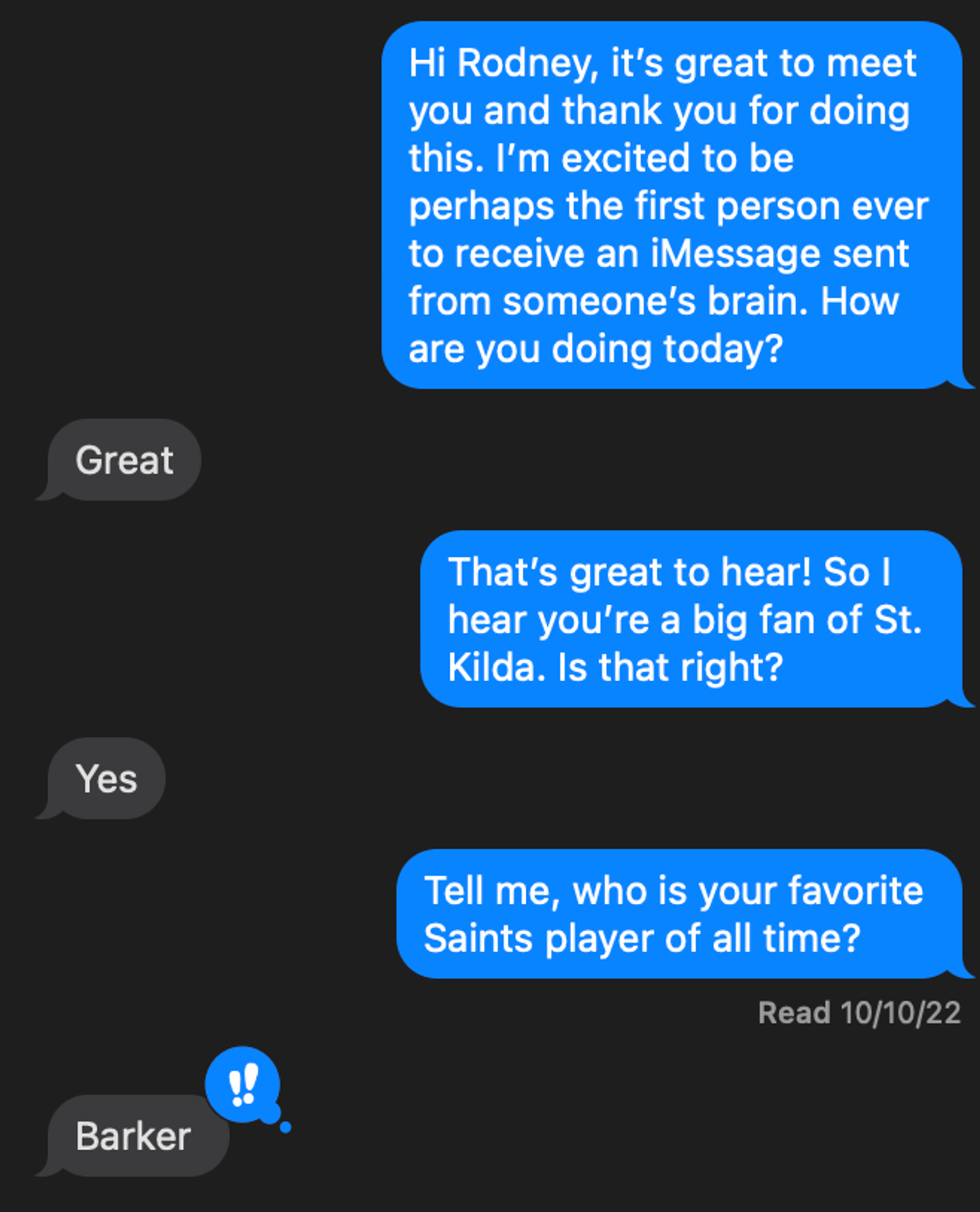

Rodney Gorham, a retired software salesman in Melbourne, Australia, sent me a text message the other day. He didn’t type, he didn’t speak. He used his brain.

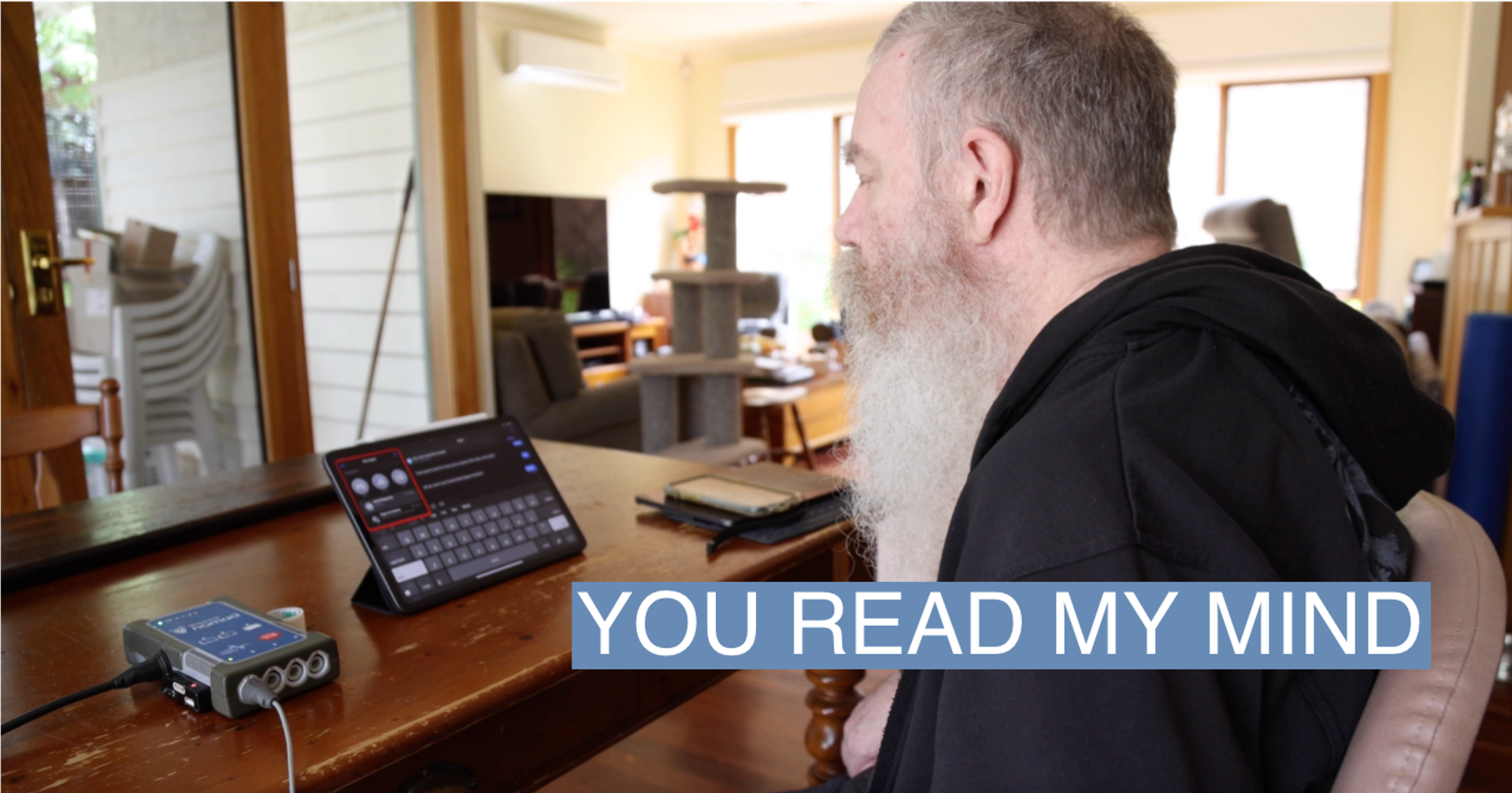

I had asked Gorham, who suffers from the debilitating disease ALS, how he was doing. “Great,” he wrote on an iPad, using a device surgically implanted in his brain at Royal Melbourne Hospital.

New York-based Synchron, which makes the device, is also the first company to gain approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to run clinical trials on a computer-brain implant.

Synchron has six patients using the device, called a “Synchron Switch,” and Gorham is the first ever to use it with an Apple product, the company said. Synchron, which has raised $70 million in venture and other funding, foots the cost of implanting and maintaining the device.

“We’re excited about iOS and Apple products because they’re so ubiquitous,” said Tom Oxley, Synchron’s co-founder and CEO. “And this would be the first brain switch input into the device,” he said.

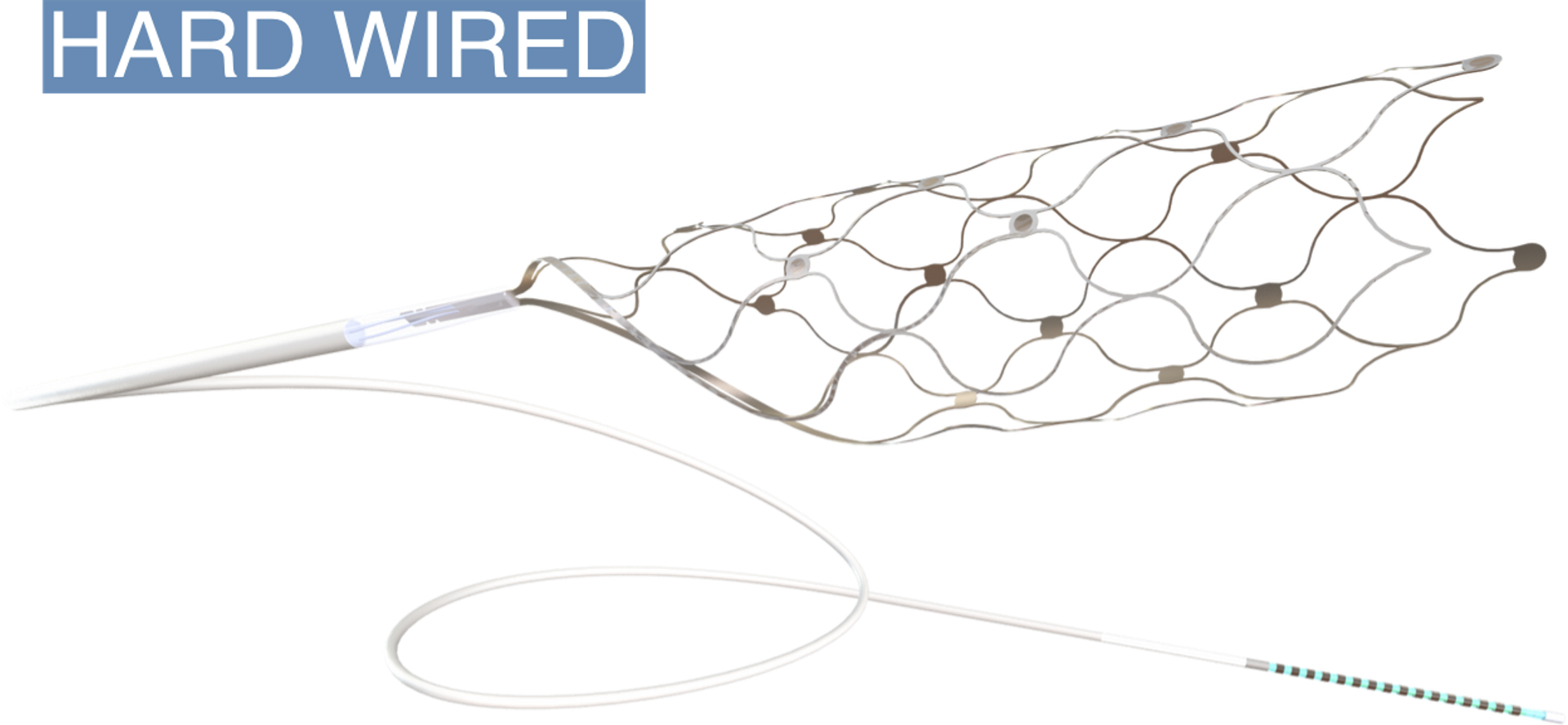

An array of sensors made by Synchron called a “Stentrode” is inserted into the top of the brain via a blood vessel in a minimally invasive procedure. It’s controlled wirelessly using the Synchron Switch from the patient’s chest.

Oxley said the skills needed to implant the Stentrode are commonplace, and that level of simplicity is key to the company’s business strategy. Implanting a device directly on the brain would require neurosurgery, a discipline with a shortage of doctors.

In essence, if the FDA approves the device for widespread use, Oxley believes computer-brain implants his company makes could become ubiquitous among people with disabilities.

For now, Synchron is keeping it simple. It isn’t trying to get patients to play pong or type 20 words a minute with their brains. Rather, it trains the device to recognize the brain signal for a foot tap. I agreed to send Gorham questions that could be answered in one word, so as not to tax him too much.

When Gorham, who loves classic cars and St. Kilda, the Aussie rules football club, thinks about tapping his foot, his iPad registers that as the tap of a finger on the screen.

Reed’s view

With Gorham’s message, an important milestone had been reached in the effort to connect computers to brains. It went from something that happens in university research labs to something that every consumer can viscerally comprehend: People can control iPhones with their brains.

Apple and Google have been waiting for this moment: The human brain could now be a peripheral device, like your AirPods or stylus.

“What’s really exciting about this project, of course, is that they’ve done something really innovative and connected it into something that’s standard,” said Gillian Hayes, a professor of informatics at University of California, Irvine.

Hayes said companies like Apple are investing in research in this area. Apple, for instance, has staff at Carnegie Mellon University where it funds research into computer-human interfaces. She said tech companies like Apple will have to figure out how to make Synchron devices work better and with less latency to speed up the process.

Everything changes when companies with $30 billion research and development budgets assign engineers to figure out the best way to allow companies like Synchron to interface with their operating systems.

Synchron has raced ahead of its competition in this area by, in essence, being practical. With its Stentrode running across the middle of the brain, the sensors don’t have a comprehensive view of the data that constantly emanates from it. But it has enough for a minimally viable product.

Neuralink, a company founded by Elon Musk, has laid out, to much fanfare, its goal of allowing humans to control iPhones with brain implants. Neuralink’s implants provide more fidelity into what’s going on by including more sensors that penetrate the brain tissue. It has demonstrated its tech with a monkey playing a videogame with its brain.

Researchers at UC Berkeley developed tiny sensors that can be sprinkled like dust inside the body to detect signals from the nerves. Those researchers founded a company that was acquired by Japanese pharmaceutical company Astellas in 2020.

The problem so far with those approaches, as impressive and ambitious as they are, is that the human body has a way of messing them up. Scar tissue can build up around the sensors, which block signals and create other problems. Or the body can reject the sensors altogether - not good when they’re attached to the brain.

Synchron’s implants are meant to be permanent and have lasted more than one year in at least four patients and the company says there have been no reported serious adverse events related to the device.

Other companies have attempted to do the same thing without entering the body, by reading brain waves from outside the skull. Microsoft’s research arm has eight people working on such a project.

To date, those efforts haven’t been able to get the same kinds of signals as ones that involve implants. Once those faint electrical signals pass through the skull, they’re a big, jumbled mess, like standing in the parking lot of a football stadium and trying to listen for individual voices.

Synchron seems like a middle ground approach. It doesn’t place sensors directly on the brain, but it gets its sensors close enough by inserting them through the jugular vein, which runs right over the middle of the brain, where the motor cortex is.

For my third and final question for Gorham, I asked him to name his all-time favorite St. Kilda player. “Barker,” he typed with his brain. That’s Trevor Barker, a star from the late 70s and 80s who died of cancer at 39. St. Kilda named the “Best and Fairest” award after him.

Room for Disagreement

The advent of computer-brain interfaces has the tendency to set off alarm bells for those worried about privacy and other related issues.

“It raises existential problems and philosophical problems and in a way that makes one feel guilty for even discussing them because there’s an obvious benefit to an overlooked and marginalized community,” said John Seberger, a Drexel University professor who researches the intersection of technology and society. “We want to make the world better through technology and that desire can be blinding, particularly if the demonstrable benefit is to a population that is marginalized.”

An article in the AMA Journal of Ethics argued that brain implants raised too many issues to be regulated just by the FDA. It suggested a new committee or regulatory body should assist in overseeing the advent of the new tech.

The View From Europe

Europeans, who are often ahead of the United States on privacy, have been thinking about how to regulate computer-brain interfaces for at least five years now, considering questions like whether brain waves should be legally considered personal data or health data.

In 2020, the committee on legal affairs and human rights for The Council of Europe called for “ethical charters, mandatory regulations, or even new rights” to address the advent of computer-brain interfaces. “Progress and innovation should not be stifled. Nevertheless, research should be steered away from foreseeably harmful or dangerous areas and towards positive applications,” the committee wrote.

Notable

- A handful of companies are building devices that read signals from the nerves and brain without any kind of procedures. These “non-invasive” devices are safe and cheap, but with current technology, they aren’t able to gain the same kind of fidelity as devices implanted in the body.

- This kind of brain research really has its roots in the 1800s, according to this comprehensive New York Times article on computer-brain implants. Today, we’re seeing the culmination of more than 100 years of curiosity and scientific breakthroughs inching us closer to the melding of mind and machine.