The News

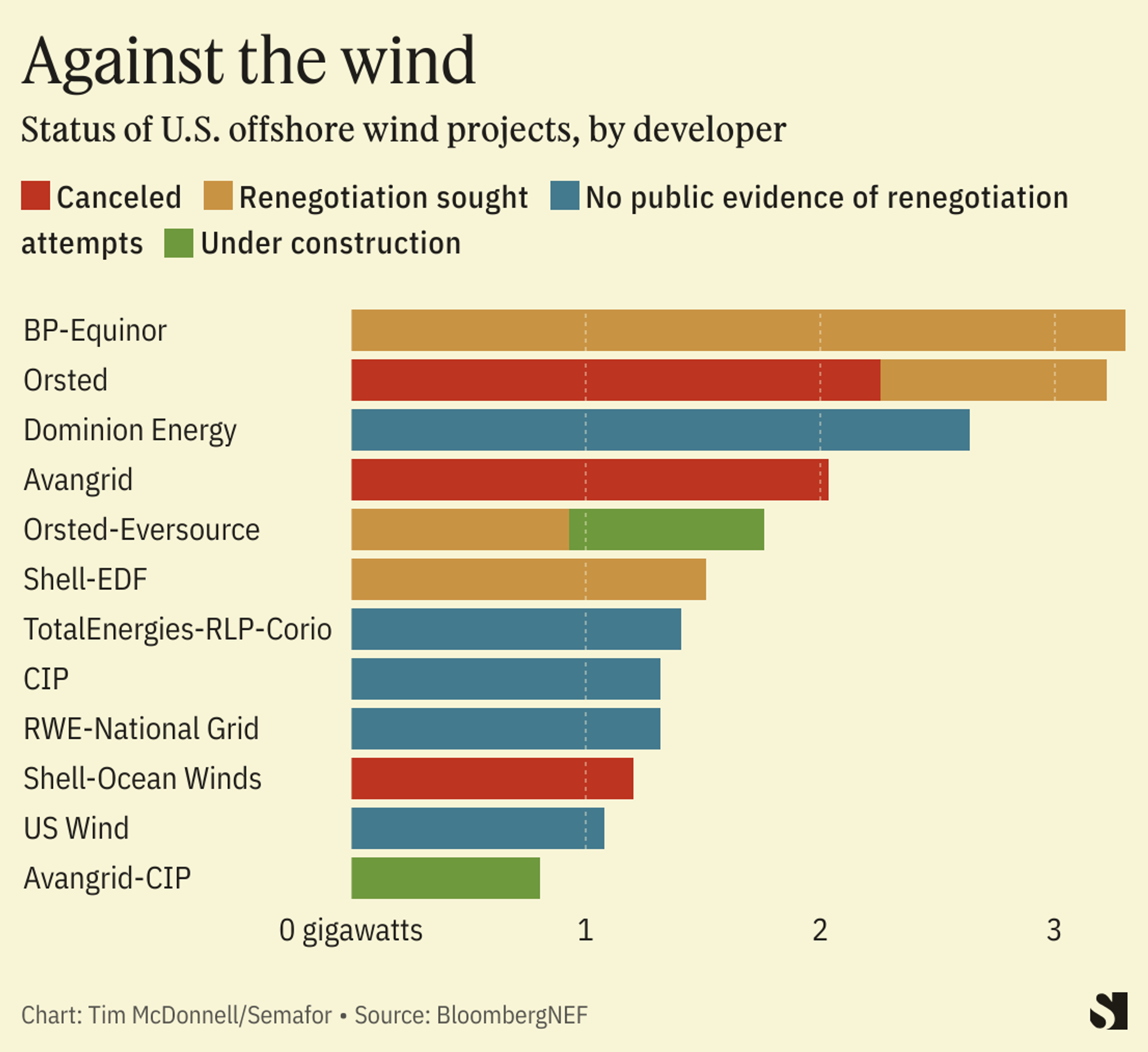

Offshore wind insiders are raising an alarm about yet another increasingly costly bottleneck for the beleaguered industry: The subsea cables that deliver the turbines’ electricity to the onshore grid. It’s one more difficult item on the industry’s long list of problems — inflation, bureaucracy, high interest rates — that have led to a recent string of cancellations, bidderless lease auctions, and multi-billion-dollar writedowns, including the cancellation on Wednesday of two planned New Jersey offshore wind farms by Danish developer Ørsted.

Tim’s view

Offshore wind developers are running into two problems with subsea cables: There’s a looming shortage of them, and they’re increasingly expensive to insure. The problems are connected, and are likely to get worse — further delaying offshore wind deployment and likely leading to higher final power costs for consumers — as cost pressures on developers mount and wind farms get larger and further offshore.

Globally, offshore wind got a slow start, with projects concentrated in China, the U.K., and a few European countries. In the last few years, many more have joined the fray, including the U.S. and Vietnam, leading to a rush on cables. The 10-year forecast for offshore wind cable demand doubled between 2018 and 2023, to about 95,000 kilometers, according to Rameeza Duggal, a senior cables analyst at the consulting firm 4C Offshore.

There are only a handful of companies that manufacture these cables, and they’re fully booked out. It used to be common to sign a cable supply deal two years before breaking ground on an offshore wind project, Duggal said. Now the norm is a decade, making it extremely difficult for anyone new to enter the market.

Technology changes are exacerbating the problem. As farms get bigger and further offshore, cables must also become bigger, longer, and higher-voltage. That results in a seemingly never ending series of upgrades and tweaks to manufacturing equipment, holding up the supply. Rather than churning out generic cables en masse, manufacturing equipment is now often built to spec for specific contracts, according to Hakan Ozmen, executive vice president of projects at Prysmian Group, one of the world’s top cable manufacturers.

It all adds up to a lot of risk for project developers. And although supply and demand are currently fairly well matched, cable supply shortages are likely to cause project delays later this decade, Duggal said.

At the same time, shifting cable specs can spook insurers, Ozmen said. That might cause premiums to go up. The cost of insuring a midsized offshore wind farm can run above $400 million over its lifetime, and at least 85% of claims relate to the cost of repairing cables or lost revenue due to cable failure, according to Global Underwater Hub, a U.K. trade group that represents companies that build cables and other subsea infrastructure. As some cable manufacturers cut costs and speed up production, they’ve become a major liability to the industry, said Neil Gordon, Global Underwater Hub’s chief executive.

“When you start driving costs out of the projects, you’re always looking to squeeze. You’re always looking to make everything cheaper, and that can affect the quality,” he said. “With cables, there’s been a high incidence of insurance claims, to the point where they’re almost becoming uninsurable.”

There are a lot of ways for cables to go awry, most often because they get damaged during installation or by fishing trawlers or storms. As the cabling industry grows, Gordon said, it needs to set higher standards to prevent damage and assuage insurers. But that’s difficult because none of the various players — manufacturers, installers, etc. — are keen to accept responsibility.

“The data isn’t public, and it’s quite a litigious industry,” Gordon said. “So we don’t exactly know where the problem is happening.”

Room for Disagreement

A spokesperson for Ørsted said the main root problem in the case of its cancellations this week was not cable costs, but the multi-year delay of an installation vessel, and added that the company may be able to reuse or resell the cables it had booked for its New Jersey projects. There’s also no shortage of bottlenecks for the industry, Ozmen said, including permitting bureaucracy, turbine manufacturers, and shipping and logistics companies: “Even if we didn’t have cable available, it wouldn’t be the only component that’s missing.”

The View From Japan

The next big leap for offshore wind cable companies is to supply floating wind farms, which can be installed in waters too deep to attach fixed pylons. The first such project was built in Scotland in 2017, but Japan now has its sights set on being a world leader in floating offshore wind, and this week signed a deal with Denmark to collaborate on new floating projects. Floating cables are a major engineering challenge that cable companies are still figuring out, Ozmen said.

Notable

- Policymakers wishing to prop up the struggling offshore wind industry face a tough dilemma, Canary Media reports: Walk back their clean energy targets, or face the political consequences of driving up electric bills.