The Scene

LAGOS — A year ago, 25-year-old Peter Oshobor took part in an initiative that allowed up and coming Nigerian designers to exhibit only three pieces at Lagos Fashion Week. But in the period between that and his 18-piece return to this year’s edition of the event last month, he has presented a collection in New York and Atlanta, and produced work for a client on a Victoria’s Secret tour.

The rise of designers like Oshobor makes the case that African fashion is in a boom era, as an inaugural report published in October by Unesco on African fashion trends argues. Increased demand has come from “an expanding urban middle class in Africa and international buyers, who both value the originality and quality of African design and craftsmanship,” the report said, estimating annual African textile, clothing, and footwear exports at $15.5 billion.

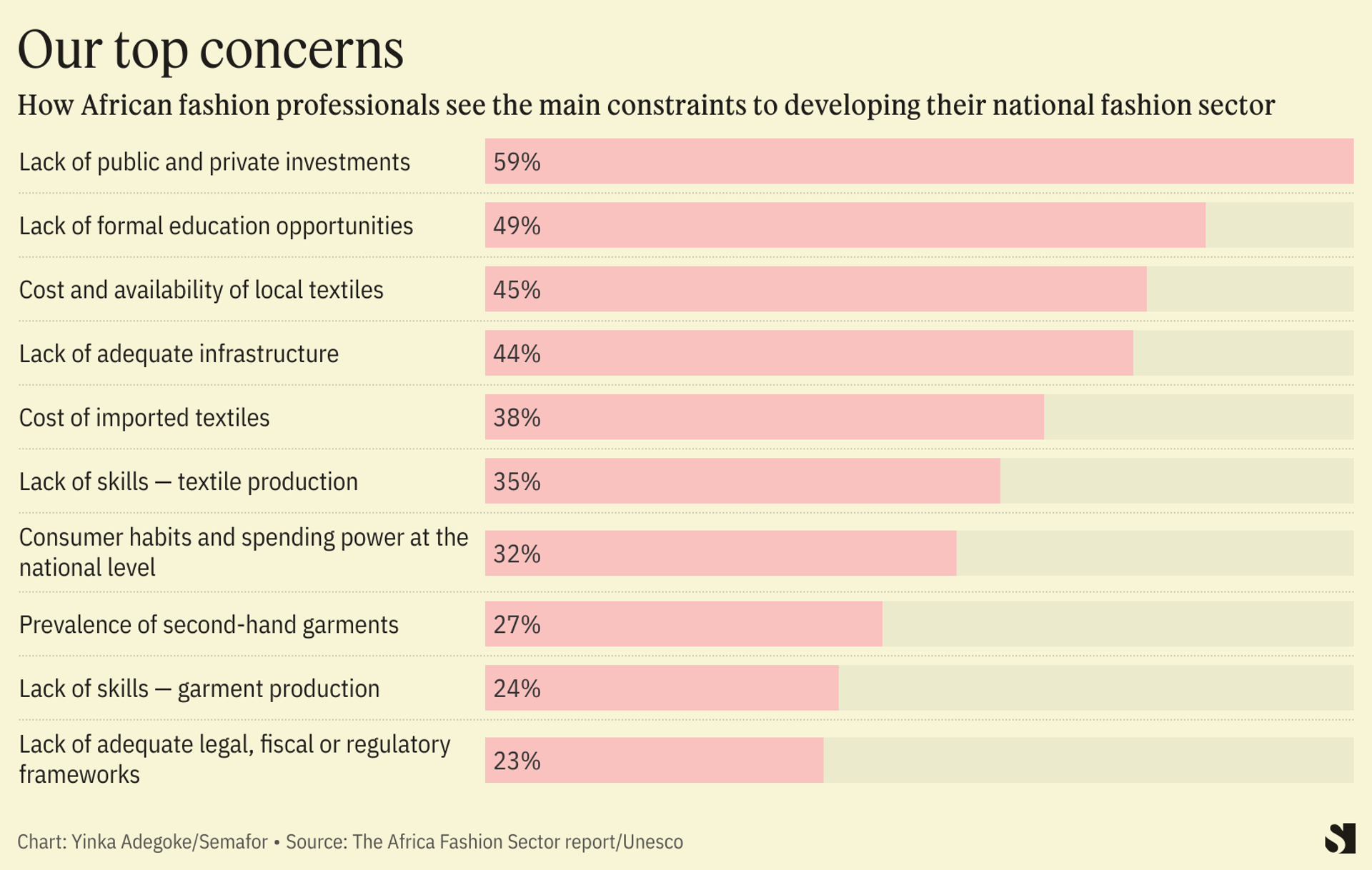

But Africa’s potential is still held back by myriad challenges. Africa-based designers are constrained by poor infrastructure, sparse investment, limited intellectual property protections, difficulties accessing new markets and sourcing quality materials, the report said. Unesco estimates that Africa’s textile, clothing and footwear trade deficit is $7.6 billion, a consequence of decades of policy changes that stifled local production, inviting an influx of second-hand clothing from abroad.

“While the textiles and garments sector is the second largest sector in the developing world after agriculture, a lot of its potential is still waiting to be realized in Africa,” the report said.

Know More

Hand-made designs crafted to be worn by upper middle class career professionals and fashion enthusiasts have become a favored product of many African fashion houses. But industrial-scale production for the mass market is on the rise too. An example is in Rwanda where Asantii rolls out thousands of ready-to-wear garments from a 24,000 square foot plant powered by over 4,000 staff.

African fashion can be understood as linkages between four sectors, per Unesco’s classification: textile sourcing, garment production, high fashion and haberdashery - the making of accessories like zips and buttons. Each faces challenges peculiar to activities involved, but multiple issues like logistics and strenuous customs processes cut across the board, designers say.

“It’s actually easier to deal with someone in the UK and US than someone within Africa,” Mai Atafo, founder of his eponymous Nigeria-based brand, told Semafor Africa. “The excise duties for sending goods from Lagos to Nairobi doesn’t make it profitable for a business.”

Alexander’s view

It would seem that Africa’s fashion entrepreneurs are making giant strides in spite of a minefield of obstacles that should discourage them. For one, institutional funding on the scale flowing to African film, music and technology startups has yet to consider fashion a noteworthy investment category. That compels brands to bootstrap towards stability against the tides of costs and competition, while constantly scrambling to find capable staff willing to commit to long periods of engagement.

“Fashion is a very capital intensive industry in which you can have so much money tied up in stock,” Iona McCreath, who leads Nairobi-based brand Kiko Romeo, told Semafor Africa. She said retailers are generally risk averse and prefer a consignment model where a retailer stocks the goods and only remits to the designer as they sell on to customers. “You have to front those costs as a designer. It gets very expensive,” said McCreath.

African fashion brands are pushing through nonetheless with a long-term view. McCreath, who took over the reins at Kiko Romeo in 2018 from her mother, sees signs of longevity in the increasing number of people wearing African designers everywhere and acknowledging their quality. Navigating limitations in sourcing has spurred innovations in textile production. An example is the Dakala, a fabric invented from scraps of denim and other waste materials by Nkwo Onwuka, founder of an eponymous brand in Nigeria.

Unesco’s report recommends an active role for African governments in improving the business of fashion, through tax incentives, social engineering campaigns that encourage patronage and representing the fashion ecosystem’s needs in national development plans. Designers would welcome these but “governments would do well by simply guaranteeing security to enable us to move freely to buy and sell, and providing steady electricity,” Onwuka said.

Room for Disagreement

Some of the growth challenges up and coming designers face in Africa stem from gatekeeping by insiders and figures atop the food chain who influence buying decisions in important circles, the young Nigerian designer Peter Oshobor believes.

“You know how we say the rich get richer and poor get poorer? Same happens in our industry. Sometimes your talent and creativity don’t seem enough to get you into places you deserve to be in. People at the top keep recycling their own because they want to remain there. So it takes lots of struggle and stress to rise.”

The View From Dar es Salaam

Industrie Africa, a website that has grown from an online magazine and digital showroom into an easy-to-use online store for African fashion, plays a crucial role in helping designers maximize the global reach of their work. A part of its senior team operates out of Tanzania’s commercial capital Dar es Salaam, managing inventory for between 40 and 50 designers from over a dozen African countries.

“Our marketplace model was built to accommodate some of the challenges designers often face,” Alice Sam, Industrie Africa’s chief growth and revenue officer, told Semafor Africa. “We encourage designers to be flexible on quantities and adjust production to meet shopper demand, and we operate on a seasonless model to fit the needs of clientele in both hemispheres. We also strive for above-standard margin splits with our designers.”

Notable

- A debut bridal collection by Washington D.C.-based Congolese designer Anifa Mvuemba received critical acclaim after its launch last month. Born in Nairobi, 32-year-old Mvuemba represents African fashion’s diaspora who, though based in developed countries, invite audiences to reconsider prejudices about Africa through the creative and colorful energies expressed in their designs.