The Scoop

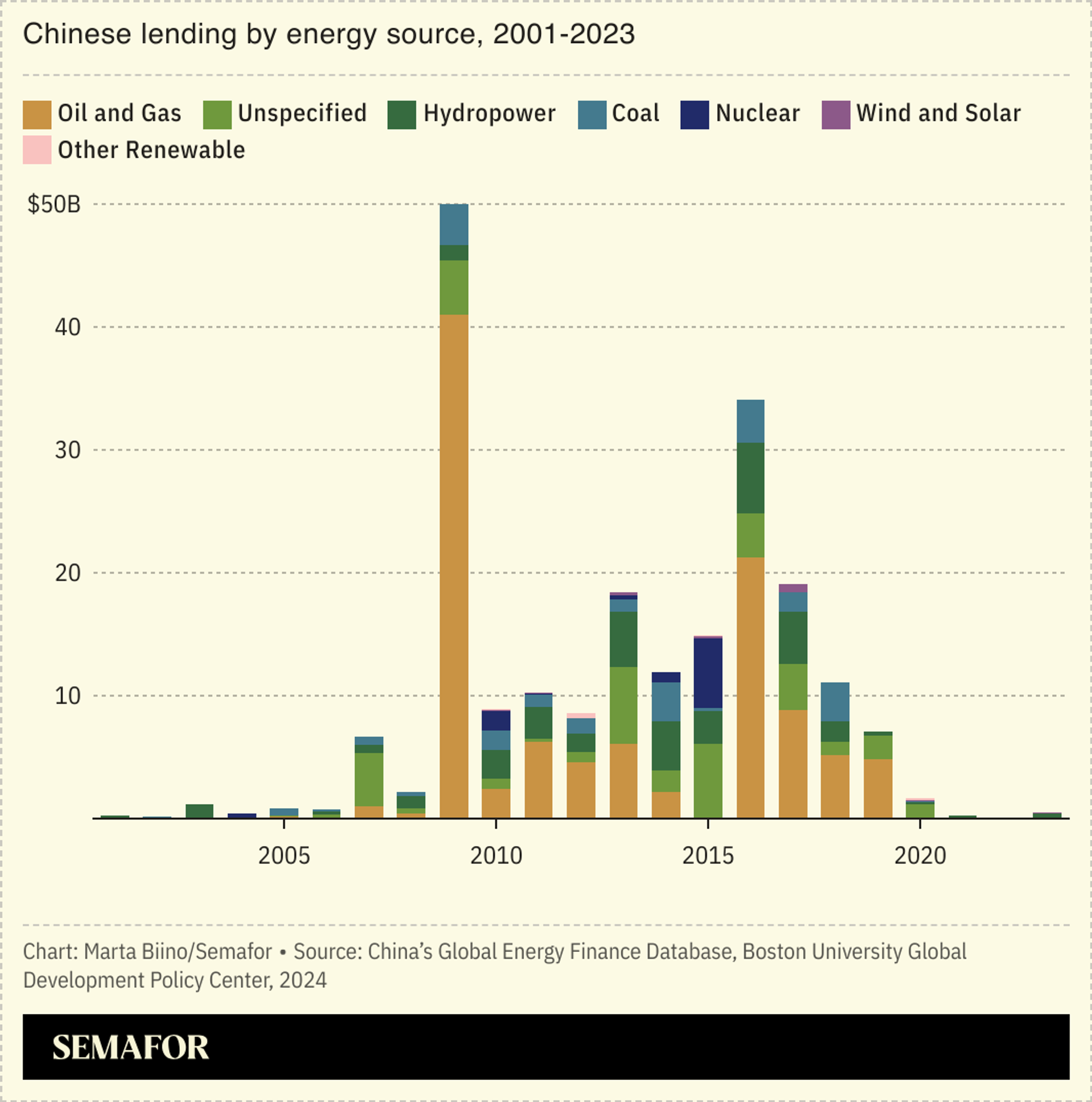

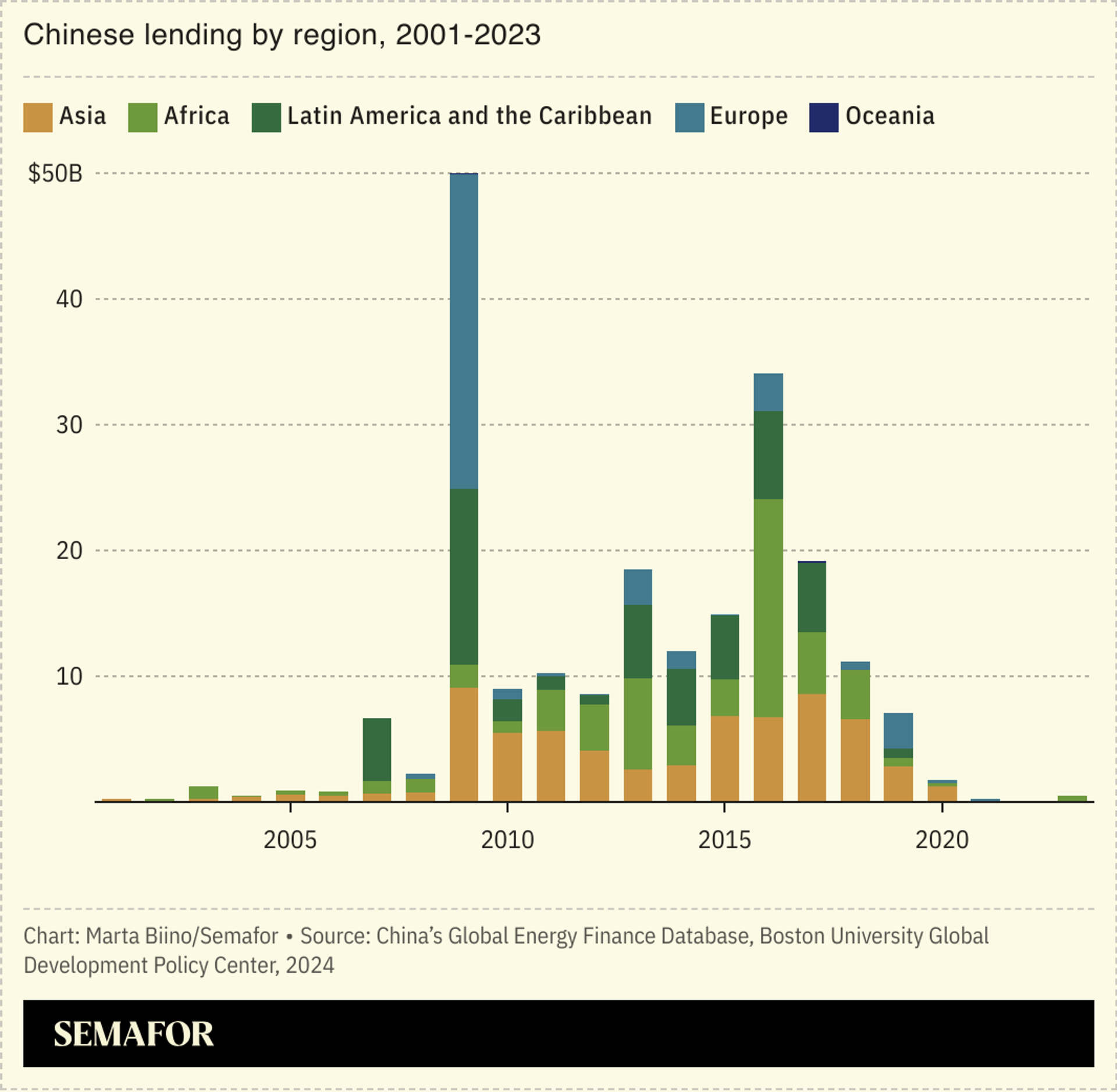

China is slowly ramping back up its program of energy-related lending to developing nations, albeit with two major shifts: Beijing’s loans are greener, and smaller. That’s according to new research published by Boston University’s Global Development Policy Center and shared with Semafor.

The figures reflect a cautious return by China to funding energy projects that were once a staple of its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), the globe-spanning infrastructure push widely seen as a way to cultivate influence. Lending had ground to a halt during the pandemic and remained near-zero since as a result of the country’s slow economic growth.

“The Chinese government did learn from the past: Huge, mega-level fossil fuel projects create controversies, create criticism, and it’s bad for its image for an international climate leader,” Jiaqi Lu, one of the authors of the report, told Semafor. “They are trying to explore new pathways in the energy financing field.”

In this article:

Know More

China made just three energy-related loans in all of 2023, a far cry from its energy lending as part of BRI in the two decades prior, during which China typically made more than 15 loans annually.

Yet, according to Lu and his colleagues, the latest data signal China’s shifting priorities: All of its loans in 2023 were for green projects, all were smaller than the historical average — from 2000-2022, Chinese energy loans averaged $574 million; in 2023, the total loaned that the year was $502 million — and all pointed to more risk-averse lending than Beijing’s overseas development banks had previously taken on.

The overall number of loans should soon rebound, Lu said, with China announcing dozens of renewables deals during its FOCAC summit with African leaders in September. More could also begin going to Latin America as Chinese lenders increasingly prioritize financial returns and avoiding political risks, meaning they may shun some African countries they previously worked with.

But individual deals will probably remain smaller than during the BRI energy lending heyday because, he said, renewables deals tend to be smaller and in many of the countries that China is considering investments, the grid infrastructure is unable to handle larger projects anyway. The overall breakdown of where China lends — about 30% to Asia, a quarter to Latin America and Africa respectively, and the remainder to Europe — is unlikely to change substantially.

“Chinese investors… are more aware of the risk compared to the 2010s,” Lu said. “They’re increasingly more cautious with their investments.”

The View From Central Asia

Around 31% of China’s energy-related lending went to Asia between 2000 and 2023, and its shifting focus is already apparent in Central Asia: Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, previously host to Chinese fossil fuel and infrastructure investments, have since 2018 seen growing interest from Beijing’s development banks to finance green projects like wind and solar farms. According to the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, Chinese banks have also shifted from primarily financing these projects with debt to doing so with equity, because the former had fuelled dissatisfaction in the countries.

Though the pivot to green financing was in large part driven by China’s own priorities, it was primarily spurred by the two countries’ “interest in renewable energy, prompted by concerns about energy insecurity and environmental pollution,” a Carnegie report noted.