The Scene

In the spring of 1995, U.S. lawmakers were becoming concerned that material uploaded to the nascent internet might pose a threat to national security. The Oklahoma City bombing had happened several weeks earlier, drawing attention to publications circulating online like The Big Book of Mischief, which included instructions on how to build homemade explosives.

Worried the information could be used to orchestrate another attack, then-Senator Dianne Feinstein pushed to make publishing bomb recipes on the internet illegal. The effort sparked a national debate about “Open Access vs. Censorship,” as one newspaper headline put it at the time.

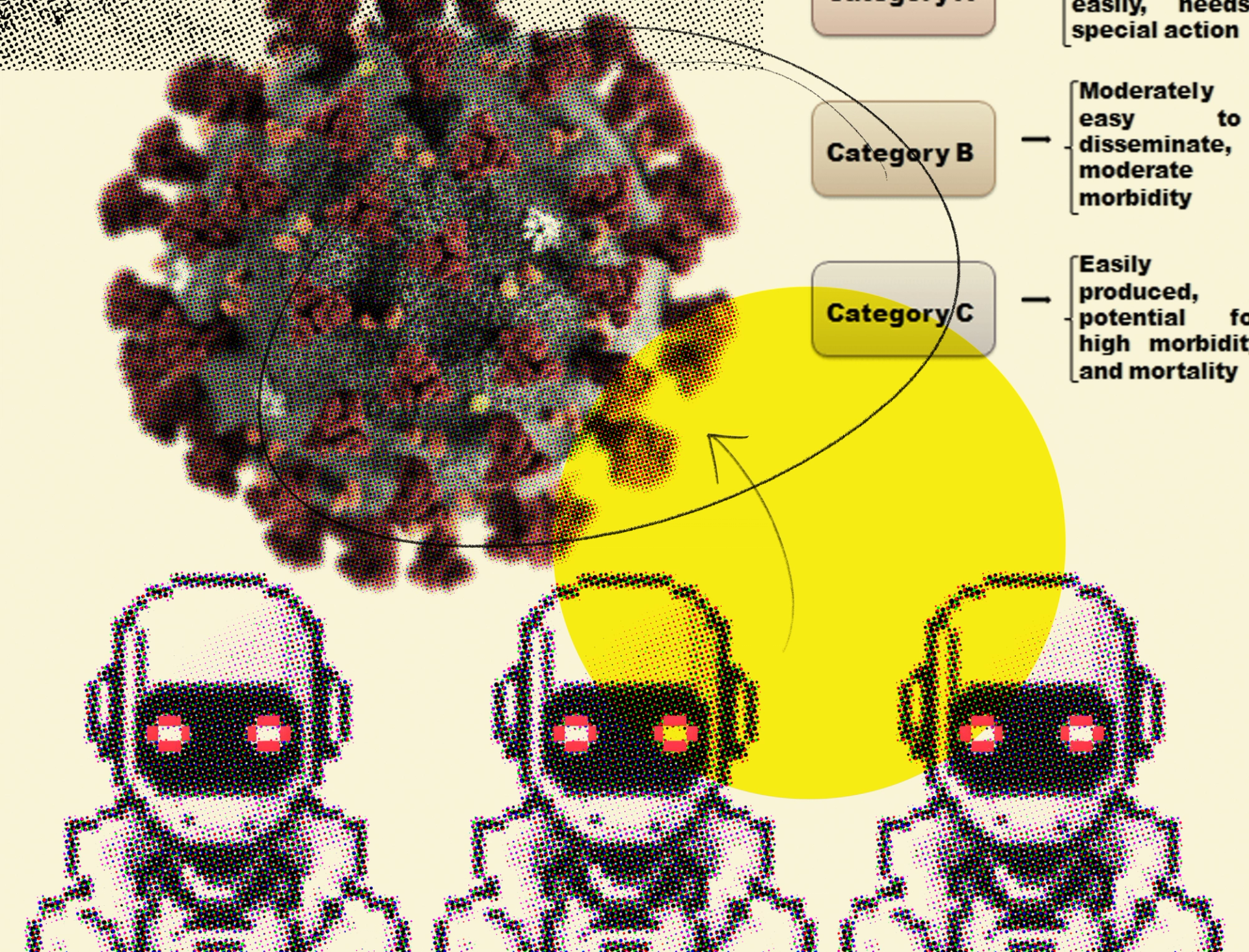

Nearly 30 years later, a similar debate is now unfolding about artificial intelligence. Rather than DIY explosives, some U.S. officials and leading AI companies say they are increasingly worried that large language models could be used to develop biological weapons. The possibility has been repeatedly cited as one reason to be cautious about making AI systems open source.

In a speech earlier this month, Vice President Kamala Harris invoked the specter of “AI-formulated bioweapons that could endanger the lives of millions.” She made the remarks two days after the White House issued an executive order on AI that instructs the federal government to create guardrails on using the technology to engineer dangerous biological materials.

Dario Amodei, the CEO of AI startup Anthropic, similarly told Congress in July that AI could be misused in the near future to “cause large-scale destruction, particularly in the domain of biology.” His warning echoed concerns raised by OpenAI, think tanks such as the RAND Corporation, and an Oxford University researcher who claimed that “ChatGPT could make bioterrorism horrifyingly easy.”

But unlike the homemade bombs Congress was worried about in the 1990s, which had already killed hundreds of people, the idea that AI would make it easier to build a biological weapon remains a hypothetical one. Some biosecurity experts argue the complexity associated with engineering deadly pathogens is being underestimated, even if you have a powerful AI tool to help you do it.

“With new technologies, we tend to project in the future as though their development was linear and straightforward, and we never take into consideration the challenges and the contingencies of the people using them,” said Sonia Ben Ouagrham-Gormley, an associate professor at George Mason University who has interviewed former scientists in both the U.S. and Soviet Union’s now-defunct biological weapons programs.

In this article:

Louise’s view

There isn’t enough evidence yet to support the argument that large language models will increase the risk of bioterrorism, especially compared to using a traditional search engine to find the same information. One promising study by researchers at RAND tried to measure whether AI tools would give bad actors a meaningful advantage, but the final results have yet to be released.

But let’s say that a terrorist group did use AI to generate thousands of new, potentially lethal pathogens, as one group of scientists did with chemical substances. The next step would be to individually test in a laboratory whether any of those viruses or bacteria could be synthesized in the real world, let alone remain stable enough to disseminate.

The group would then need to figure out a way to spread the weapon while ensuring it remains potent. Bacteria and viruses are highly sensitive to their environment, and something as simple as the pH level of the water they’re in can kill them or change their properties.

After the pathogen is deployed, it would still be impossible to predict ahead of time how it might interact with human populations, said Michael Montague, a senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security. He pointed out that even though COVID-19 has been intensely studied around the world, virologists can’t reliably anticipate the impact each new strain might have.

Ben Ouagrham-Gormley said her research has shown that achieving each of these steps requires employing different, highly-trained experts, including people who specialize in the exact type of pathogen being used. An AI model might be able to replace some of their work in the future, but she argued it can’t replicate the hands-on wisdom that comes from working in a laboratory.

“This kind of tacit knowledge exists everywhere, but in the bio field, it’s really important because of the fragility of the raw material,” Ben Ouagrham-Gormley said.

When I began reading the work of AI researchers concerned about risks related to biological weapons, I found they rarely mentioned any of the arguments I just outlined, which came from people who specifically study biosecurity. LLMs have applications in many different fields, and paying closer attention to voices from each of them will lead to a better understanding of the technology’s potential downsides.

There are also lessons to be gleaned from the history of the internet, which is full of attempts to democratize information while also trying to reduce the real-world harms that could come as a result. In the late 1990s, Congress did end up making it illegal to share bomb instructions in narrow circumstances, but the law seemingly wasn’t very effective.

Room for Disagreement

Rocco Casagrande, managing director of the biosecurity and research firm Gryphon Scientific, said that what he and his team of biologists found when they evaluated Anthropic’s chatbot Claude and other large language models made them concerned.

“These things are developing extremely, extremely fast, they’re a lot more capable than I thought they would be when it comes to science,” Casagrande told Semafor.

Anthropic hired Gryphon Scientific to spend more than 150 hours red teaming Claude’s ability to spit out harmful biological information, according to a July blog post. Anthropic declined to comment further on the findings from those experiments.

Divyansh Kaushik, associate director for emerging technologies and national security at the think tank Federation for American Scientists, suggested that an AI tool fine-tuned for biological purposes could potentially pose a higher risk than a general purpose chatbot. But he acknowledged that the physical engineering part would still remain very difficult.

Notable

- An anonymous tech and science blogger, who goes by the name 1a3orn, looked at the citations for one policy paper arguing large language models could potentially contribute to bioterrorism. They didn’t find the evidence convincing, and their resulting post was shared by a number of AI researchers on social media.