The News

The final round of global talks aimed at ending plastic pollution opened in South Korea Monday, although optimism was low among delegates that a deal was on the horizon. The challenge they face is perhaps underscored by the recently decided COP29 agreement that some rich countries will pay $300 billion a year by 2035 to developing nations adapting to climate change, a sum lambasted by those countries as insufficient.

The debate in South Korea centers around three questions: Whether to limit how much plastic companies make; if chemicals tied to their manufacture should be banned; and how to pay for any eventual deal. Oil-rich countries like Saudi Arabia and other nations where a lot of the world’s plastics are made are opposed to any such limitations, while the US, where much of the world’s plastics are made, has rowed back support for caps on plastic production.

SIGNALS

The US plays ‘hot and cold’ in negotiations

As one of the world’s top plastic makers, the US has “played hot and cold” in supporting the key issues at the heart of the negotiations, E&E News reported, having earlier indicated support for curbing plastic production, before walking back that stance. Adding to the uncertainty is US President-elect Donald Trump: Plastic production relies on fossil fuels, a sector that Trump has championed. Speaking to Inside Climate News, advocates said the Biden administration should push for as strong a plastics treaty as possible, even if it is unlikely to pass the current Senate because it might in the future. “But if the outcome is a weak treaty, the diplomatic work that began a decade ago to curb plastic waste will end up in failure,” they argued.

Plastics talks raise mirror issues to those seen at COP29

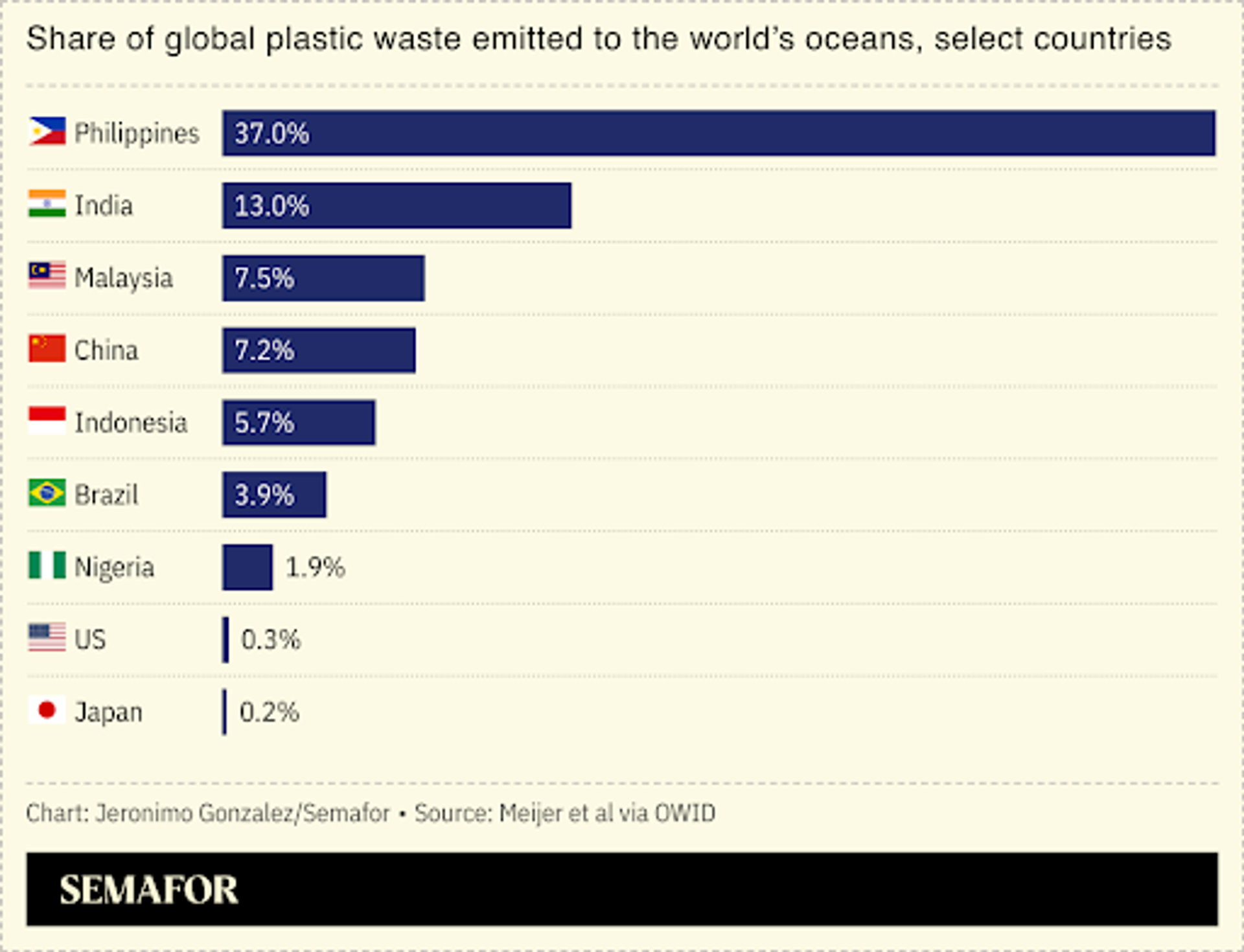

The divisions in South Korea closely “echo” those seen a COP29, where the interests of developing nations — which bear the brunt of the issues associated with plastic pollution — are pitched against those of richer nations and fossil-fuel-heavy economies. Countries like Saudi Arabia, which one analyst described as a “wrecking ball” at COP, and Russia have pushed for a treaty focused on waste management instead of cutting the amount of plastic made, a strategy one ocean policy expert suggested would be pointless: “Plastic is made at such a rate that it is impossible for waste management systems to keep up,” he wrote in The Conversation.