The News

Global HIV infection rates are dropping rapidly, a new study found, but likely not fast enough to meet the United Nations’ 2030 target to cut HIV incidence and death by 90% from 2010 levels.

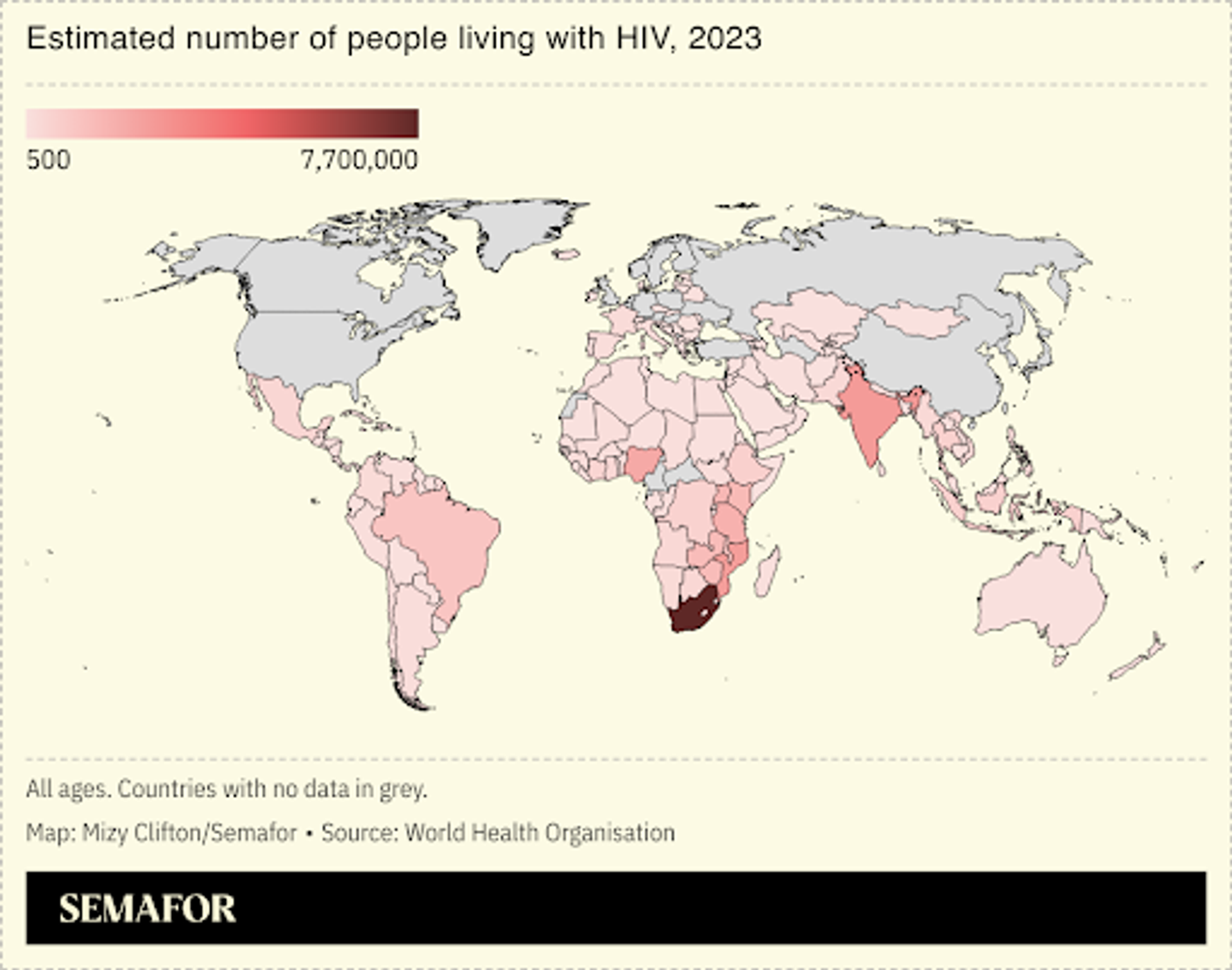

New infections dropped by a fifth between 2010 and 2021, while HIV-related deaths fell by 40% in the same period. Preventative treatments are driving the decline, with the most precipitous drop in new infections seen in South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa, the study found, although overall rates of infection remain highest there.

New vaccines are raising hopes that the disease may soon be eradicated; one recent clinical trial in Africa found a twice-yearly injection of an antiviral drug protected young women from the disease: “Africa is excited, women are excited, we have waited long for this,” one Ugandan healthcare worker told The New York Times of the trial.

SIGNALS

Africa’s progress must not breed complacency, health advocates say

Africa has borne the brunt of the global HIV pandemic; with the greatest number of people infected and the extremely high cost of early treatments, for years most all infected people were expected to die from HIV/AIDS. Now, most people infected with HIV are receiving some treatment, The Economist wrote, with the majority of gains being seen in Africa. Yet the success has come with a danger of complacency, a public health advocate with the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria warned: “There is a diminishing sense of urgency.” The battle to reach the UN’s 2030 target still faces significant roadblocks, he added, including stigma, gaps in prevention measures, and the criminalization of homosexuality in some African nations.

Eastern Europe is an outlier — Russian influence could be the reason

Global HIV infections are diminishing, but in Eastern Europe and Central Asia, AIDS-related deaths have risen 34% since 2010, The Guardian reported, while the new study also found similar “worrisome trends.” Russia’s hardline approach to drug use and the LGBTQ population, as well as a proliferation of Kremlin-inspired laws in neighboring countries that put stricter controls on foreign charities and organizations, have significantly hampered prevention and treatment efforts in the region, public health advocates told the outlet. Russian influence is “clear and growing,” Michel Kazatchkine, the special adviser to WHO Europe, said.