The News

The bankruptcy of one of Europe’s most promising and high-valued climate tech companies is forcing a rethink of how best to compete with China in the EV supply chain — and whether trade barriers work.

Sweden-based battery maker Northvolt was the great hope both for Europe’s clean tech manufacturing renaissance, and the bedrock of European automakers’ EV aspirations. It was also a high-profile rebuttal to the US Inflation Reduction Act, meant to show that Europe could compete with the US for investment while competing with China on battery technology. The company, Europe’s first home-grown EV battery maker, drew nearly $15 billion in investments, had more than $50 billion in battery orders on its books, and was working toward a $20 billion stock listing.

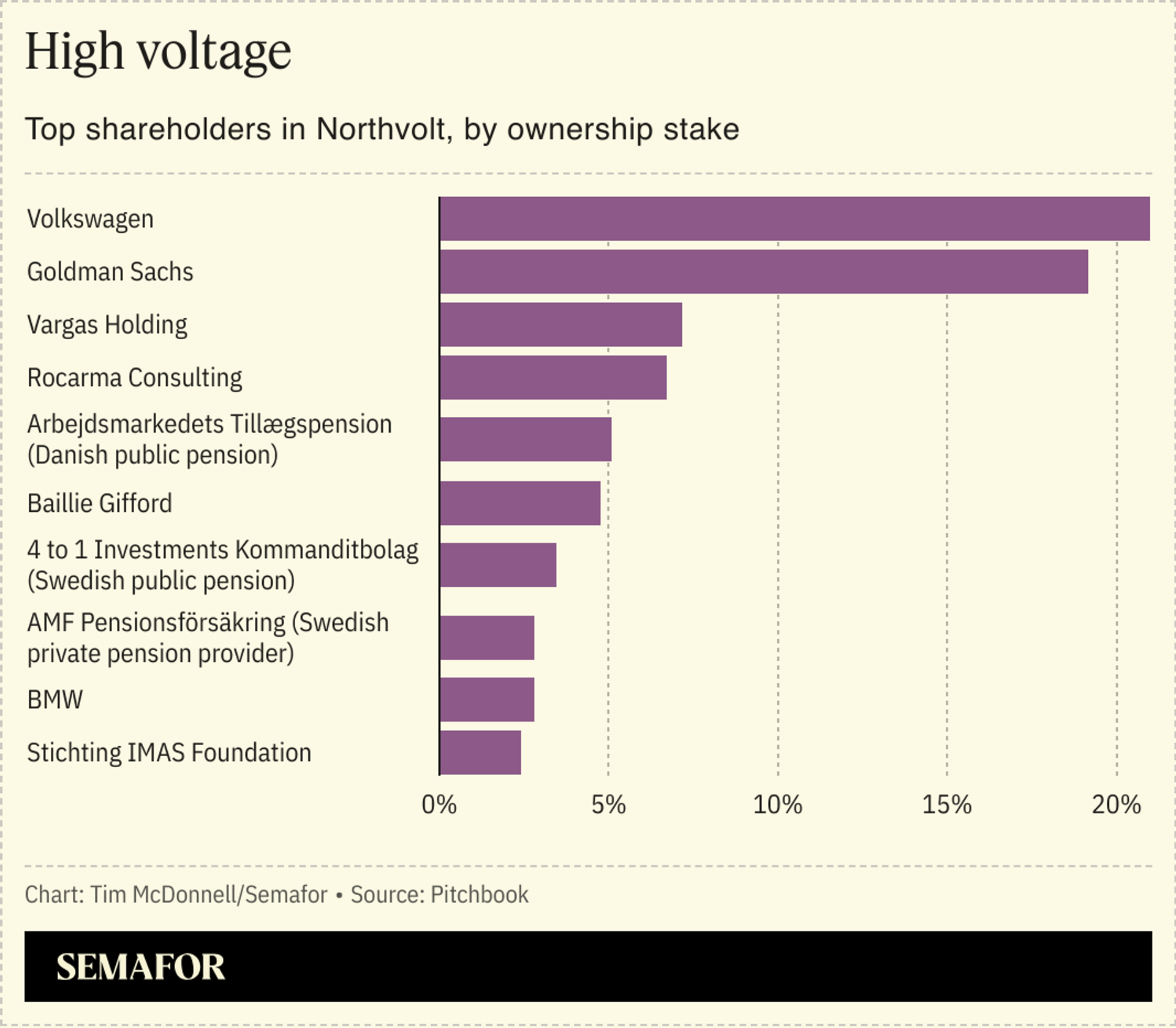

Then things began to fall apart. Following a string of safety incidents, gaping production shortfalls, and missed delivery deadlines, the company was last week down to its final $30 million in cash — about a week’s worth of operating expenses — and nearly $6 billion in debt. Northvolt filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection, and co-founder and CEO Peter Carlsson, who previously oversaw Tesla’s supply chain, stepped down. Left holding the bag were backers like Volkswagen, which said on Monday that its €1.4 billion stake in Northvolt is now worth less than half of that, and Goldman Sachs, which will reportedly take a $900 million loss.

In this article:

Tim’s view

Northvolt’s collapse is proof that even lavish public subsidies — the company pocketed nearly $1 billion from Germany — and booming customer demand aren’t enough to break China’s vise-grip on EV tech, and evidence that a new strategy is needed in order for Northvolt and peers in Europe and the US to survive.

In the battery world, scale is everything. Northvolt’s only hope for beating Chinese giants like CATL on cost was to grow as quickly as possible, a philosophy that led the company to start work on four gigafactories in three countries even when the first was barely functional. It was also racing to expand beyond conventional lithium ion batteries, where China’s dominance is strongest, into nascent areas like battery recycling and sodium batteries where it could more easily find a competitive advantage and break free from Chinese raw material suppliers.

There were a few problems with that approach. The company rapidly burned through cash in a way that “wasn’t really prudent,” Bill Sonneborn, president of the clean tech investment firm Generate Capital, told Semafor. They were spread too thin between facilities and technologies. And they made a mistake that Sonneborn said is pervasive across climate tech: Underinvesting in the human resources needed to actually build and operate large-scale industrial facilities, as opposed to the nerdier pursuit of intellectual property.

But Northvolt’s undoing was sealed because while it was focused on avoiding Chinese raw materials, it was still perfectly eager to import large amounts of Chinese manufacturing equipment, along with hundreds of Chinese and Korean workers to operate it. That led to culture clashes, miscommunications, and hardware incompatibility issues that left the company’s flagship plant in Sweden operating at about 1% of its production capacity — meaning it couldn’t begin earning revenue to offset its big spending. Northvolt didn’t respond to a request for comment.

The lesson from Northvolt is that trade barriers and subsidies aren’t enough to stand up battery plants that can compete with China, because they don’t solve the overarching problem — that Chinese firms control most of the necessary technology — said Jonas Nahm, a political economist at Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies. Northvolt would have fared better if it had more in-house manufacturing experience, rather than being hamstrung by its Chinese equipment suppliers.

The only way to get there in a timely manner, Nahm said, is for US and European policymakers to find ways to replicate and build on Chinese manufacturing tech, not just close the door and leave domestic producers to start from scratch. Instead, he said, they should look for ways to trade what China wants — access to lucrative Western markets — for the R&D the new crop of domestic manufacturers need. That might mean opening the door for greater Chinese investment, not closing it off, or forming training partnerships for Western engineers with Chinese companies, Nahm said.

On Monday, Trump threatened to slap an additional 10% tariff on all goods coming from China. That measure is aimed more at punishing China for what Trump describes as its role in the global drug trade, rather than supporting US companies. But those tariffs are likely to make US clean tech manufacturers less, not more, competitive, Nahm said.

“Policymakers are bad at predicting when alternative supply chains will be available,” he said. “The Trump tariffs are hugely disruptive for the ability to stand anything like this.”

Room for Disagreement

Northvolt isn’t down for the count, and in fact the bankruptcy may be the best thing to happen to the company in a long time, Sonneborn said, since it will lower the company’s cost of capital and eliminate a decent chunk of its debt.

Notable

- The Biden administration extended a $6 billion loan to EV maker Rivian on Monday, part of its last-minute push to support clean tech companies before Trump takes office.