The News

Syrian President Bashar al-Assad’s overthrow had near-immediate global reverberations on migration and drug trafficking.

At least eight European nations suspended processing of asylum applications for Syrian nationals a day after Assad’s ousting. Meanwhile, officials told The National that manufacturing of Captagon, an amphetamine-like narcotic whose production was concentrated in Syria, had all but halted. The drug was a major source of income for the ruling elite in Damascus.

SIGNALS

Syria set the stage for European anti-migrant populism

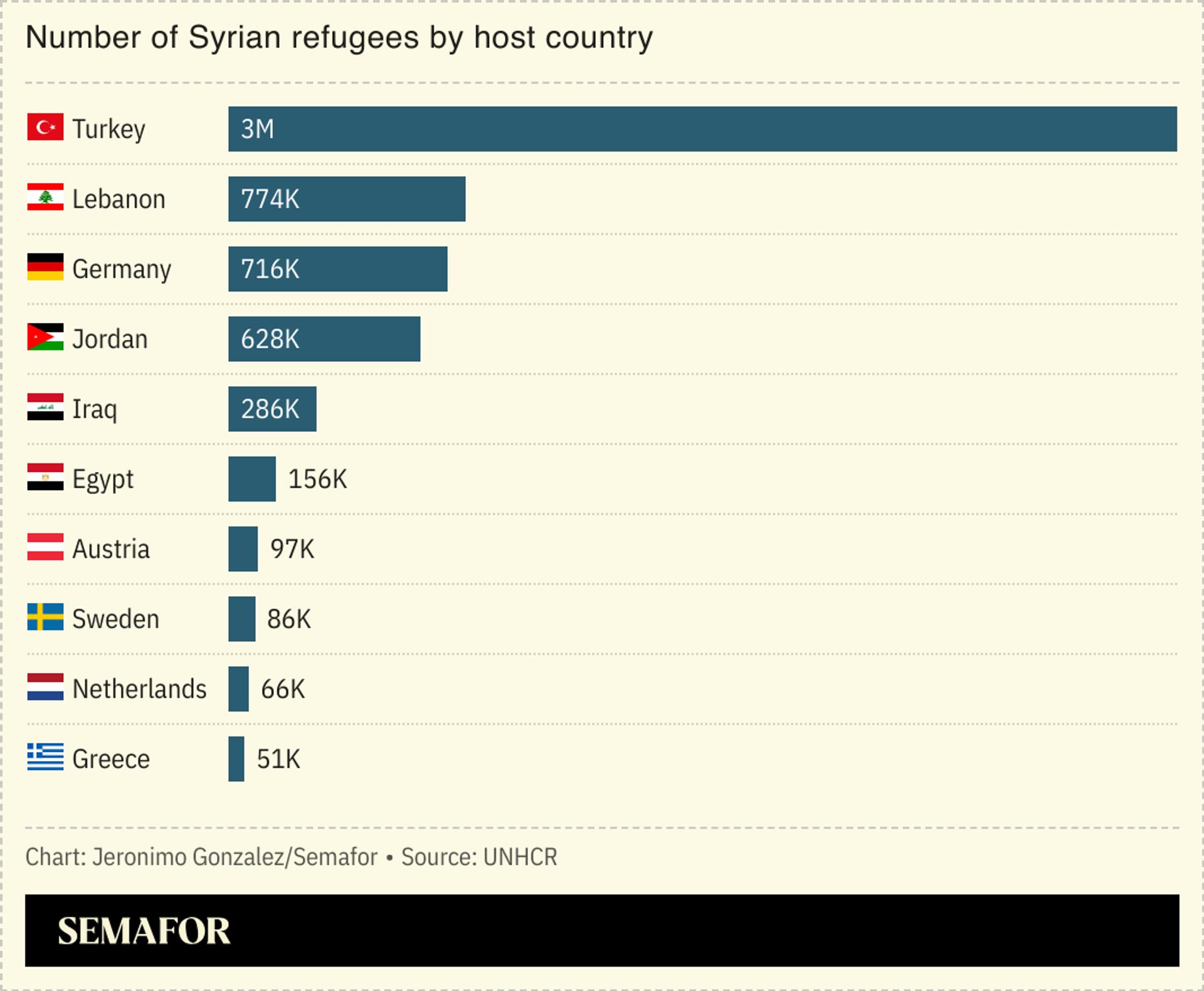

The rapid fallout from Assad’s ouster points to how “Syria broke the world,” the journalist and historian Kim Ghattas wrote in the Financial Times, including by contributing to a European migration crisis that has defined politics on the continent for the last decade. More than 4.5 million Syrians have made their way to Europe since the onset of the 2011 civil war, and the country was still the top origin nation for asylum seekers entering Germany this year, Politico reported. Far-right political parties have surged in popularity on a mandate of anti-immigrant policies. “The refugee crisis roiled the politics,” Ghattas said, “and set the stage for Brexit.”

Uncertainty remains on what a free Syria will look like

Though most Syrians are pleased about Assad’s fall, some are concerned over the plans of the rebel successors Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), and their leader, Abu Mohammad al-Jolani. Uneasy questions over Jolani’s human rights record, which includes accusations of torture and mass killings of prisoners in HTS-controlled areas “eerily resembl[e] allegations against the Assad government,” Foreign Policy wrote. There is a risk that for a region clouded by warfare this year, silver-lined Syria could fall into the same patterns it was known for under 60 years of dictatorship. Even Syria’s drug trafficking economy is liable to quickly start up again: “Captagon will be an appealing quick-fix for cash,” an analyst told The National.