The News

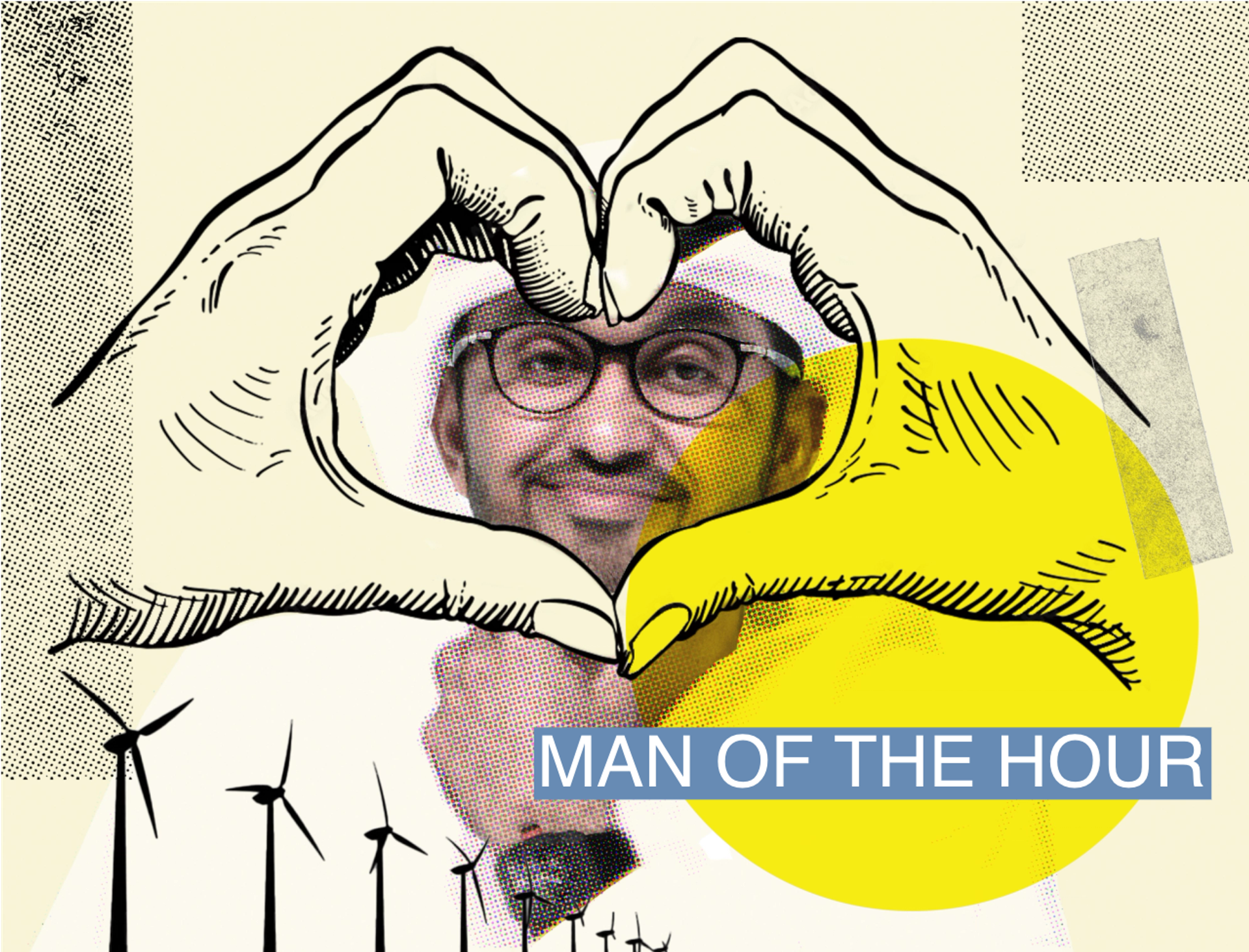

COP28 President Sultan al-Jaber has achieved something unprecedented for an oil executive: Winning fans among climate activists.

Al-Jaber was by far the most controversial COP president in the summit’s three-decade history. The 50-year-old Emirati, who also runs the country’s national oil company and its media investment fund, was described by environmental groups in the run-up to COP as a “ridiculous” choice with “the most obvious conflict of interest there can be.” Al-Jaber seemed to confirm their fears in a string of mini-scandals including communications documents suggesting he might use the summit to broker oil deals and public comments that appeared to question the scientific basis for phasing out fossil fuels.

But when the summit wrapped up on Wednesday with the first-ever global agreement to “transition away from” fossil fuels, al-Jaber had played a vital role in one of the most significant breakthroughs in the history of international climate diplomacy.

In this article:

Tim’s view

Al-Jaber proved uniquely placed to bring recalcitrant fossil-fuel producers like Saudi Arabia into the consensus. Now, with the summit concluded, some previously-skeptical environmentalists are willing to admit that the agreement’s language on fossil fuels shifted their view of al-Jaber, and that a diplomatically astute fossil-fuel executive, counterintuitively, may have been exactly what COP needed to finally directly address the primary causes of climate change.

“Despite facing initial skepticism due to his background, Dr. Sultan’s commitment to open dialogue and understanding diverse viewpoints was instrumental in shaping the outcomes and fostered an unprecedented level of consensus,” Harjeet Singh, head of global political strategy for the activist group Climate Action Network International, told me. “His leadership at COP28 marked a significant shift towards more effective climate negotiations.”

Al-Jaber may be one of the world’s most experienced leaders in dealing hands-on with the hard choices of the energy transition. The UAE, while clearly still a major oil and gas exporter, is more economically diversified than most of its Gulf neighbors or other OPEC member nations. Among al-Jaber’s many other hats is that of a renewable energy exec, having founded the Emirati clean-energy firm Masdar. It’s easy to imagine him making a case behind closed doors to these peers in support of the transition that would be far more credible than if it came from a European country or other more conventionally climate-friendly government.

At the same time, the COP’s outcome proves that the summit’s success or failure was never up to al-Jaber to begin with, said Alden Meyer, senior associate of international climate policy at the think tank E3G.

The open secret of any COP summit is that the final agreement — although it sends an important political signal about the long-term trajectory of the global economy — is ultimately toothless without specific national policies to back it up. Over the next couple of years, Meyer said, the U.S., China, and other top emitters need to scale back their fossil-fuel production plans, encourage private investors to shift more into clean energy, take more aggressive steps to curb consumers’ oil and gas demand, and finally act on a pre-existing commitment to phase out fossil-fuel subsidies.

“I admit I was skeptical when [al-Jaber] was appointed that he would be able to deliver much,” he said. But “if these things happen, the Dubai COP will join Rio, Kyoto, and Paris as one of the most consequential climate summits in the history of this process.”

Room for Disagreement

To be sure, the final COP28 deal fell short in many regards, and lots of climate activists remain suspicious of al-Jaber. A post-game interview he gave this week to The Guardian in which he said that his own company will go ahead with a planned $150 billion investment in oil and gas production may serve to validate their concerns.

“Let’s not rewrite history: Sultan al-Jaber did not put the issue of fossil fuel phase out at the top of the agenda at COP28,” said Romain Ioualalen, global policy manager at the activist group Oil Change International. “This progress was achieved by decades of struggle by frontline communities, indigenous peoples, and the most affected countries, in particular Pacific nations.”

The “transition away” language in the agreement is undercut, Ioualalen said, by loopholes that are obvious handouts to the oil and gas industry, particularly in recognizing the role that “transitional fuels” — a reference to using natural gas to replace coal in the power sector — and carbon capture can play. Those references suggest al-Jaber was willing to elevate the priorities of a small group of energy producers over the 140 or so countries that had pushed for less qualified language.

“That’s on al-Jaber,” he said. “We cannot normalize the unacceptable conflicts of interest seen during this year’s negotiations.”

The View From Baku

Next year’s summit, in Baku, Azerbaijan, is certain to elicit another round of similar controversies. The country has a checkered track record on human rights, and is even more reliant on oil and gas revenue than the UAE, reaping 93% of total government revenue from fossil fuel proceeds in 2022. But its reserves are less extensive than the Gulf’s, and may be depleted within the next two decades — giving it a practical reason to embrace the energy transition.