The Scene

LAGOS — Nigerians are struggling with runaway inflation driven by the double whammy of a significant rise in fuel costs and the devaluation of the naira.

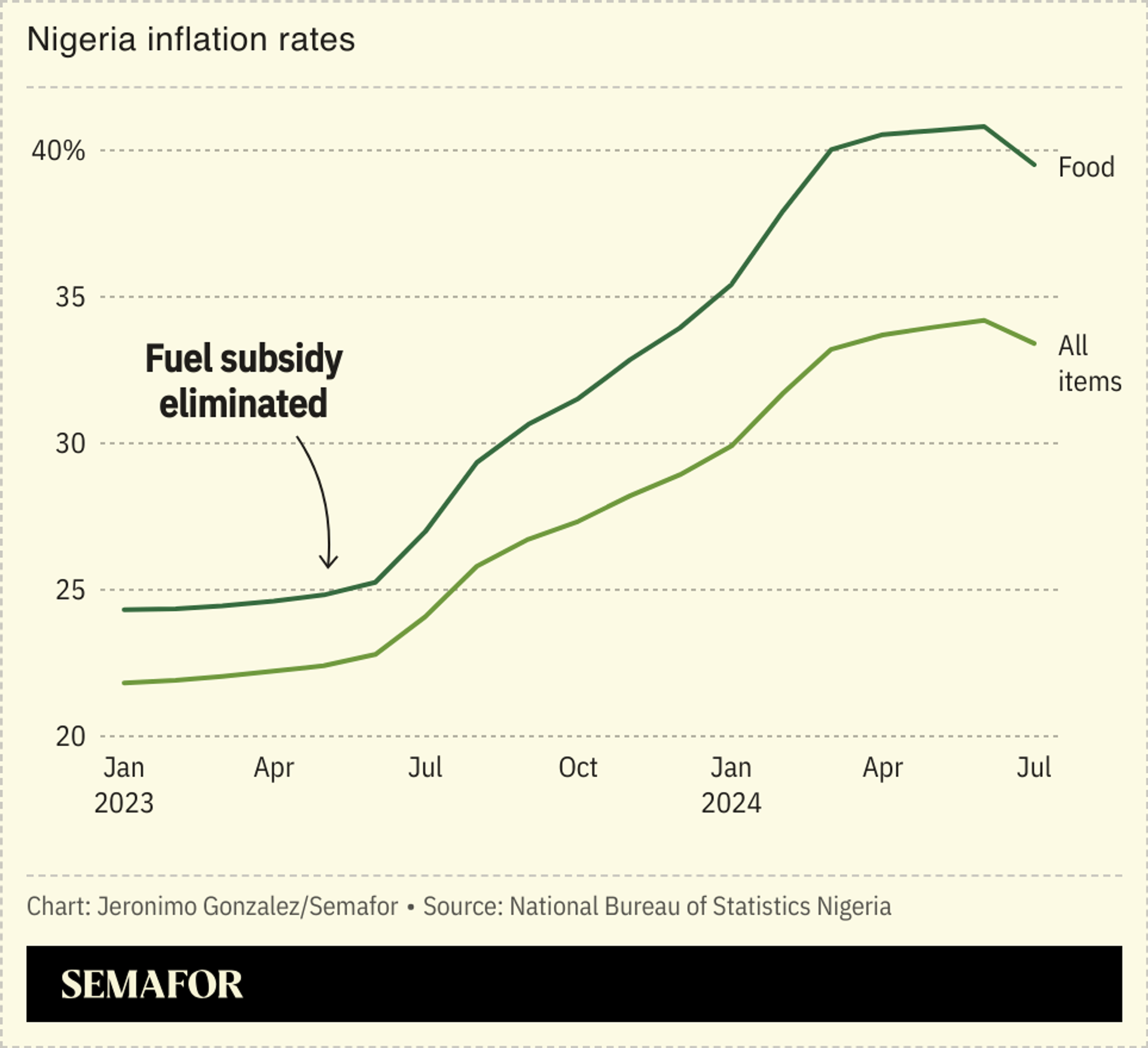

The latest official inflation figures rose to 34.6% last month — a 28-year high. But Nigerians who spoke to Semafor Africa said the situation feels even worse because prices change from day to day, making it hard for households and small businesses to make plans.

“The costs of buying fridges from importers and transporting them to our shops has been too expensive,” said Promise Ikechukwu (pictured), a refrigerators and freezers retailer in the Surulere neighborhood of Lagos. He blamed the current government of President Bola Tinubu for the challenges he faces. “During Buhari’s regime, we bought double-door fridges for 250,000 naira and sold them for 300,000 naira,” he said of business under Tinubu’s predecessor. “Now we buy for 450 and sell 500.”

Another businessman told Semafor Africa that he and other businesspeople he knew have had to focus on valuing assets at the current cost of replacing them rather than their original purchase price. In some cases they have to anticipate what goods are likely to cost as prices are changing so rapidly.

In this article:

Know More

For most ordinary Nigerians, transport costs are where the pinch of rising prices is felt most immediately. Just moving around a sprawling metropolis like Lagos is a slow and expensive task for workers. Many people have seen their daily transport costs more than double in the last couple of months driven by rising fuel prices. “I have had to increase my housekeeper’s salary twice in the last few months because transport was taking more than half her pay,” said one finance executive.

Kudirat Adisa, a mother of two with a small kiosk selling cold soft drinks in Surulere, said her sales are down due to the price rises. She said it now costs much more to buy from wholesalers and believes it’s all down to fuel prices.

Soon after Tinubu took office in May 2023, he set about implementing policies that many economists have long suggested Nigeria needed to have a genuine chance at long-term sustainable growth. The changes included ending a costly fuel subsidy and allowing the naira to float against the dollar. The naira has lost more than 70% of its value against the dollar since then.

Both changes have had a significant impact on the economy. The country’s limited rail and air networks mean it relies heavily on road transport both for consumers and commercial movement. So, as National Bureau of Statistics data shows, food prices have risen in tandem with fuel prices since the subsidy was cut.

Nigeria is also a big importer of both input products and finished goods, so the naira’s devaluation has had a notably negative impact on broad inflation.

Yinka’s view

Earlier this month I noticed there was less of Lagos’ notorious traffic congestion as I moved around the city. I was often told that had to do with the sharp rise in fuel costs. But, even if that was a correct explanation, few observers thought it was a great trade-off for a sluggish economy.

As well as fuel, the naira’s rapid devaluation has meant businesses of all sizes have struggled. Multinationals including Diageo and Lafarge have had to find buyers for their Nigeria businesses as the naira’s gyrations have confounded their local operations.

But the financial reset by consumers and business owners “is not as tough as the mental adjustment,” said veteran economist Bismarck Rewane of Lagos-based Financial Derivatives. “It’s an adjustment we’ve been through before, but this one has been particularly vicious.”

One key concern for market watchers is the central bank’s attempts to curb inflation with interest rate hikes. It’s risen to 27.50% this month from 18.75% at the start of the year. That has “resulted in eligible businesses delaying their long term borrowing plans” for investment noted Jubril Enakele, founder of Iron Capital, a Lagos-based investment bank.

Capital Economics analyst David Omojomolo is also concerned about the efficacy of the central bank’s approach, given the structural weaknesses of the Nigerian economy. “The risk for businesses going forward is interest rates staying elevated, keeping borrowing costs prohibitive,” he said. “So you could have a situation in which even if businesses get relief from inflation, they still struggle to access finance to expand.”

The View From Aso Rock

Tinubu presented a 47.9 trillion naira ($30 billion) budget for 2025 to parliament on Wednesday. The bill, his second as president, assumes a benchmark oil price of $75 per barrel and production of just over 2 million barrels per day — an output level some analysts say would be hard to achieve due to sabotage and ageing infrastructure. Budgets in Africa’s top crude producer are anchored on oil sales which make up around 90% of foreign exchange earnings.

The budget also assumes inflation will fall from over 34% currently to 15% next year.