The News

For months, the economics and financial worlds have wondered whether the U.S. would be able to achieve a historic soft landing, bringing inflation back under control while avoiding a recession. Turns out, it might have already happened.

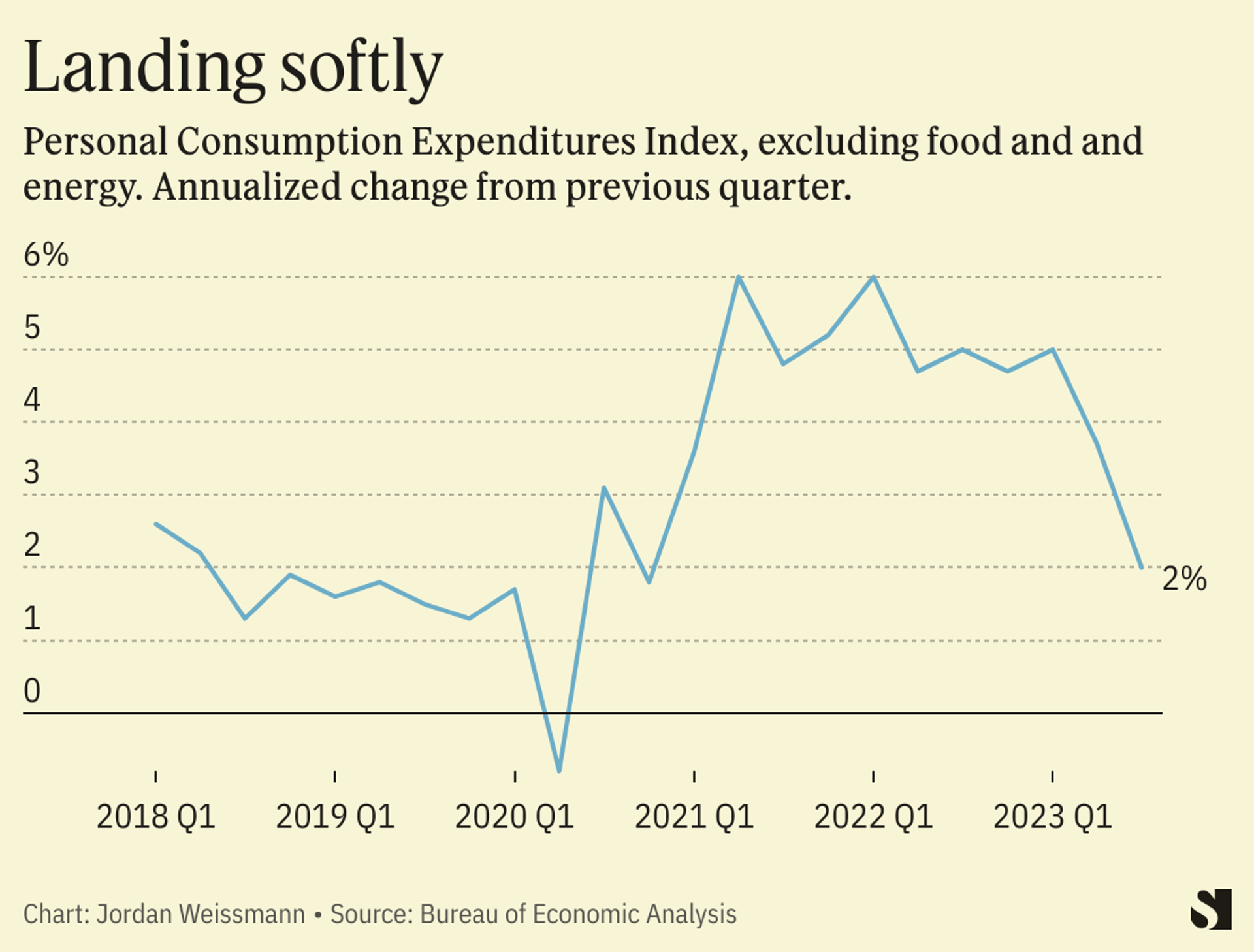

On Thursday, the Bureau of Economic Analysis released revised data showing that inflation rose at a 2% annualized rate in the third quarter of 2023 — smack dab on the Federal Reserve’s target, even as job and GDP growth remained robust. That’s based on the core Personal Consumption Expenditures Index, which excludes volatile food and energy costs, and is the central bank’s preferred measure of how fast prices are rising.

It is still possible, of course, that inflation could reaccelerate, much as it did after the government briefly seemed to bring it under control in the late 1960s and again in the early 1970s. The economy could also still weaken into a downturn, especially if growth slows and Fed officials hesitate to cut rates next year. But if the current trend holds, it will mark a rare economic turn of events that relatively few professional economists thought possible. At the start of 2023, 85% of economists polled by the Financial Times predicted a recession within a year.

The pessimism was understandable: At least since the Korean War, there is arguably no real precedent for the U.S beating the kind of inflation it experienced over the past two years without sinking into a downturn.

Step Back

The most frequently cited example of a “soft landing” took place between 1994 and 1995, when Fed Chair Alan Greenspan managed to raise rates, then cut them in time to avoid any economic damage. This is the performance that earned him his reputation as “the maestro” of monetary policy. But the key context for this feat, which often gets skipped over in retelling, was that inflation had not actually begun to pick up when the Fed began tightening. Greenspan & Co. were instead moving preemptively, because they worried that consumer prices might begin to rise.

When the Fed has tightened in response to an actual flareup of inflation, the end result has typically been recession. Sometimes, that has been a purposeful decision. The Fed triggered the painful double-dip downturn of the early 80s in order to break the back of stagflation. Other cases have involved bad luck: Princeton economist and former Fed Vice Chair Alan Blinder argues that the central bank might have pulled off “a perfect soft landing” in the early 1990s had it not been for Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait, which sent oil prices skyrocketing.

The View From Economists

Economists are sure to spend decades arguing about why this time was different, if that in fact turns out to be the case (there’s still a vigorous debate about what exactly led to 1970s stagflation). But so far, the debate has mainly split into two main camps.

The Biden administration’s economic team, among others, argue that inflation was able to come down without job losses in large part because the pandemic supply chain crisis that tangled the world economy finally subsided this year.

Others, such as former Treasury Secretary Larry Summers, have credited the Fed. By hiking rates aggressively, he argues, the central bank kept future inflation expectations in check, which prevented rising prices from turning into a self-fulfilling feedback loop.

The debate has significant near-term stakes, as Paul Krugman laid out in a recent New York Times column. If the Fed’s hikes are mostly responsible for keeping inflation in check, then there’s a stronger case for keeping rates high, which will pose a risk to growth and jobs. If supply chains are mostly the answer, then there’s less harm in cutting rates next year and trying to push the current boom even further.

Jordan’s view

There are longer-term stakes for economic policy debates outside the Fed as well. When the Biden administration first proposed its massive stimulus plan in 2021, critics like Summers suggested that it was a dangerous gamble in part because if it sparked inflation, the Fed would likely need to trigger a recession in order to bring it back down. That prediction is starting to look wrong: Fighting inflation may not require tanking the economy after all. If that’s true, it could encourage going big with fiscal responses to future downturns and crises.

Room for Disagreement

Summers still thinks it’s premature to say we’ve stuck the landing. “It isn’t clear that the landing has been soft in the sense that there are a variety of problems — declining flows of credit, inverted yield curves, aspects of consumer behavior, rising evidence of credit strains — that raise the possibility that the landing won’t be soft, if there is one,” he said this month.

Update

On Friday morning, the Bureau of Economic Analysis reported that the core Personal Consumption Expenditures Index rose at less than a 1% annualized rate in November. Over the past six months, it has risen 1.9% annual rate, just below the Fed’s target.