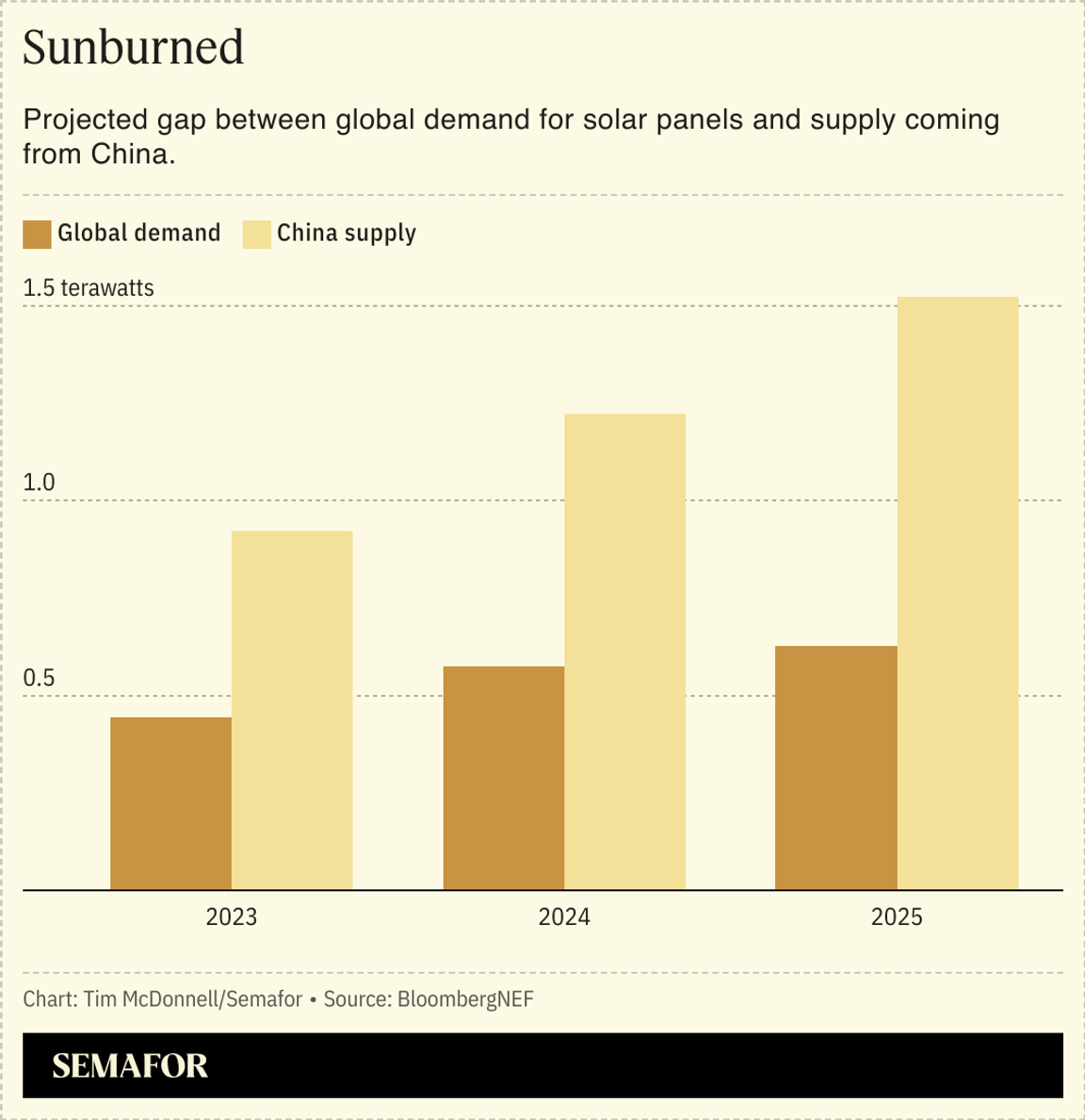

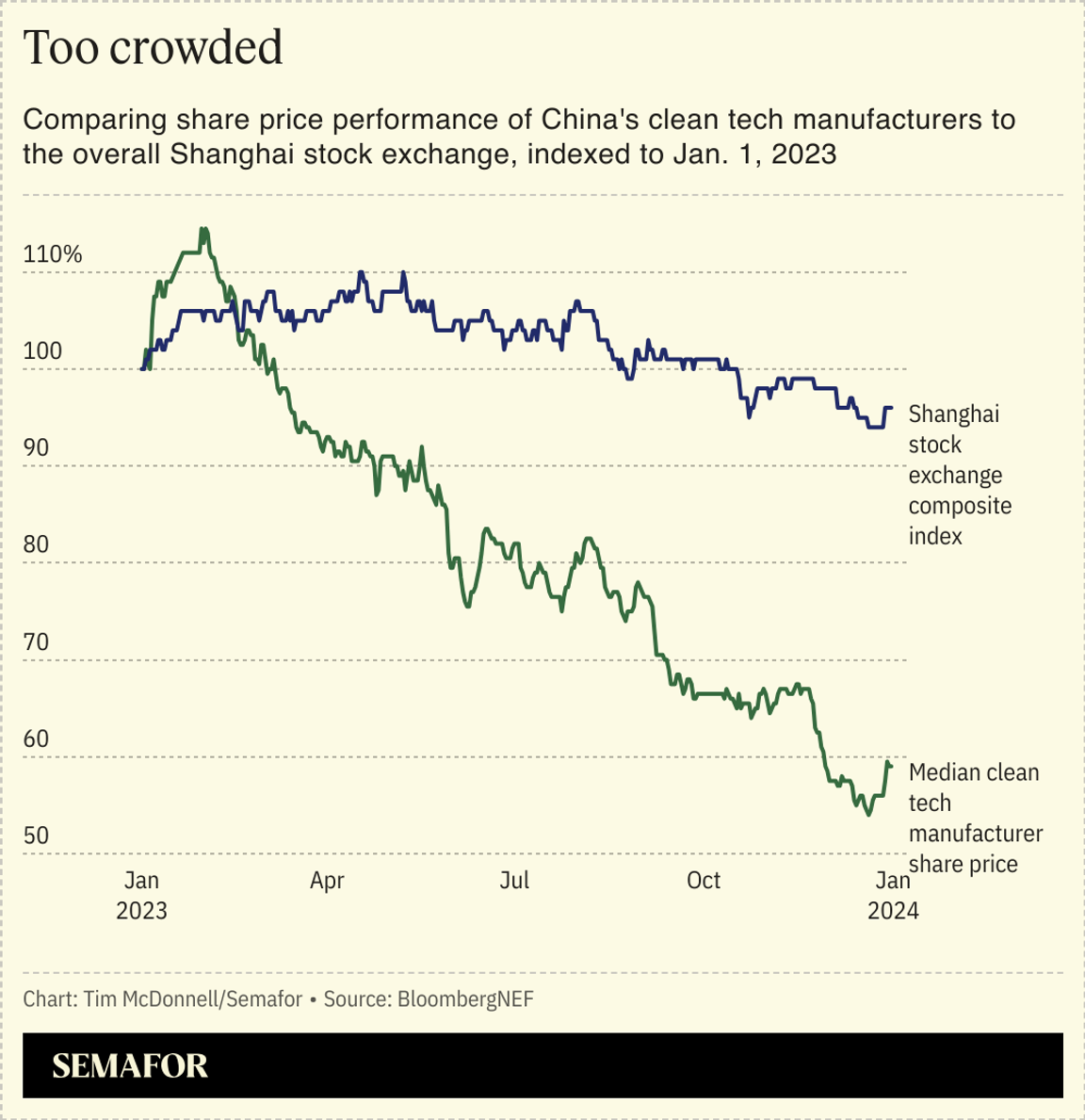

China’s capacity to produce solar panels and EV batteries has blown far beyond what the entire global economy would need even in the most rigorous decarbonization scenario, a BloombergNEF analysis found.  By 2025, the country will be producing more than twice as many panels and batteries as the world needs, as the result of what Antoine Vagneur-Jones, head of trade and supply chains at BloombergNEF, calls “off-the-chain capitalism in its rawest form, with massive, white-hot competition” between manufacturers. In general, this is good news for the climate, as the supply glut has prices plummeting. But it’s bad news for manufacturers, both within China — where share prices of cleantech companies are tumbling and bankruptcies are proliferating — and in the U.S. and Europe, where protectionist trade policies simply can’t keep pace with the supply glut. That glut appears likely to persist for the foreseeable future, Vagneur-Jones said, largely because there’s still a drumbeat of engineering innovation in the background for both solar panels and batteries, meaning that manufacturers have to continually invest in facility upgrades to keep up to date with their rivals even if new production capacity isn’t needed.  China’s manufacturing overload is undermining one of the key assumptions Western governments have been working under at this stage of the energy transition: That a small premium on locally-made cleantech, resulting from protectionist trade policies, was worthwhile from a job-creation and supply chain security perspective even if it ran counter to climate goals. That premium is now greater than anyone anticipated, and China’s manufacturing capabilities are so far ahead of the market that government subsidies for would-be U.S. competitors are nowhere near enough to make domestic manufacturing viable. The upshot is that without a significant escalation in protectionism, which invites a backlash from China on other goods, much of the $156 billion in U.S. clean tech manufacturing plans announced since the Inflation Reduction Act was passed may not come to fruition, Vagneur-Jones said. In other words, the law may fail on both rapid clean tech adoption and job creation. “Policymakers are going to have their hands forced by these market dynamics,” he said. If more aggressive protectionism is unpalatable, the U.S. may need to cut its losses on domestic solar manufacturing and redirect those resources to even greater consumer subsidies, he said. The government should also use this moment to build strategic stockpiles of cleantech hardware, which would at least serve the aim of supply chain security. |