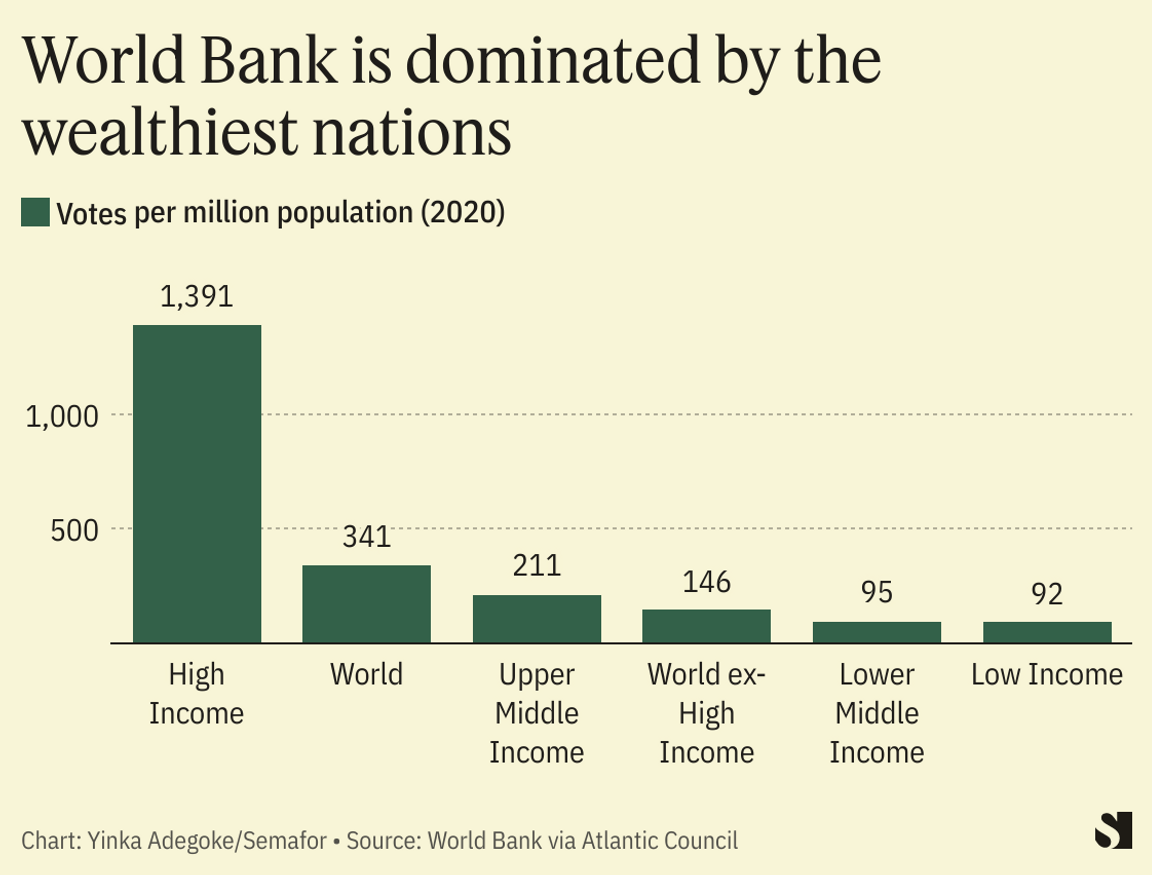

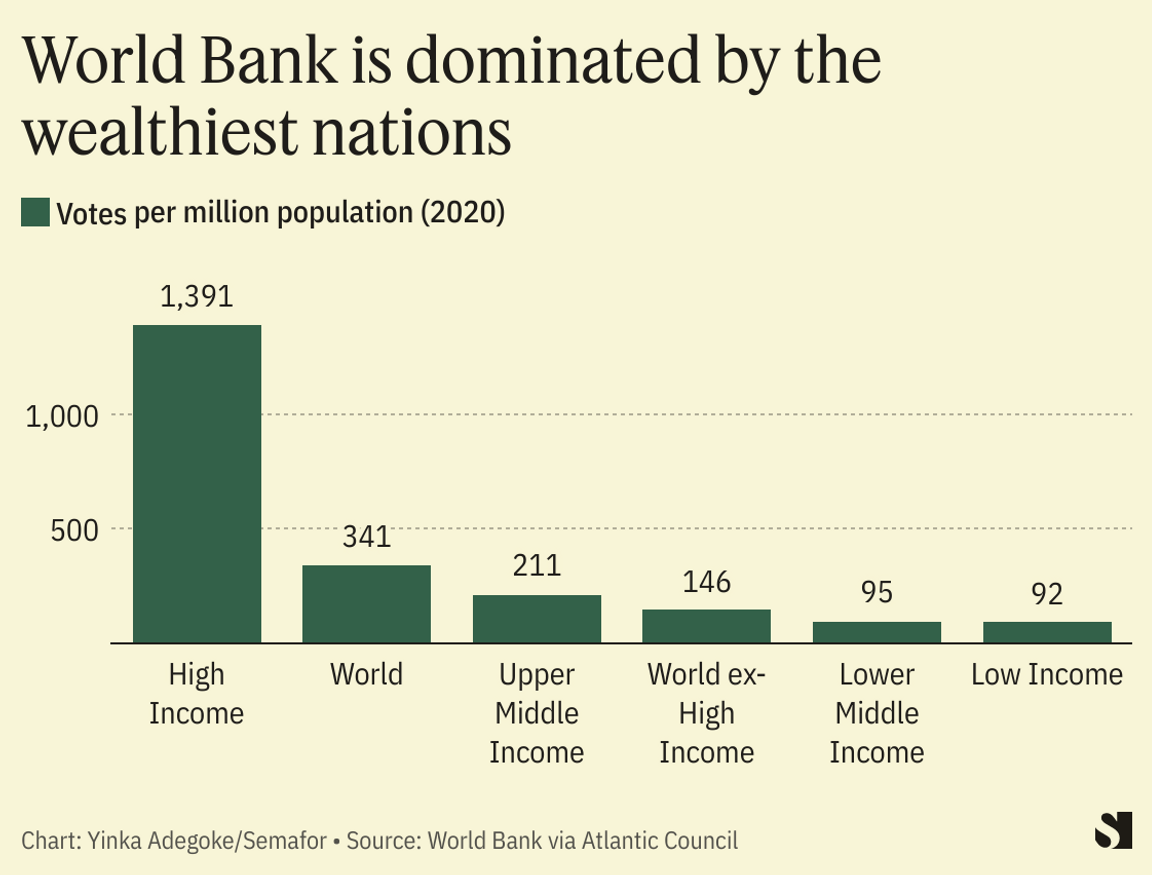

THE NEWS African countries are pushing for greater influence at the World Bank and International Monetary Fund to prioritize the needs of developing countries grappling with one of the harshest economic environments since the 2008 financial crisis. “It is time for the world to take action and create a more inclusive global financial system that works for all nations,” said Ghana’s finance minister Ken Ofori Atta, in a speech in Washington D.C. last week. “To start, Africa must have a seat at the table in the global multilateral system.”  Reuters/Ken Cedeno Reuters/Ken CedenoAbout half the economies in sub-Saharan Africa face a triple whammy this year of a funding squeeze, escalating public debt, and double-digit inflation.The inability of developing countries to access alternative sources of funding is due to the rapid tightening of global monetary policy sparked by wealthier countries trying to combat rising inflation. It has also been aggravated by a US-dollar effective exchange rate reaching a two-decade high last year, which has worsened the burden of dollar debt service payments. Calls to reform the so-called Bretton Woods’ financial institutions have grown louder in recent months as the mounting debt problem threatens to wipe away socio-economic gains of the last 25 years. The process to restructure distressed debt has been held up in countries including Ghana and Zambia, where China, a key bilateral lender, has so far been reluctant to take a “haircut” without the World Bank doing so too. African finance ministers and their teams want the World Bank and the IMF to move quicker and offer much larger support than seems possible under the current order. There are also concerns that the efforts to reform the World Bank, with an increased focus on climate change, will deprioritize poverty alleviation and end up benefiting high and middle income countries rather than low income countries. South Africa’s finance minister expressed concern at the bank’s proposed wider remit earlier this year. YINKA’S VIEW The biggest issue on every African finance ministers’ mind during the Spring Meetings last week was the risk of a debt crisis in the region. Even if you were one of the few sub-Saharan African countries not on the official distressed debt or high risk list, you would have to be concerned because there’s a real risk of contagion, certainly when it comes to perception. I moderated the Atlantic Council event where Ghana’s Ofori-Atta pulled few punches about the ineffectiveness of the World Bank and other multilaterals in this critical moment. He said the system was failing to solve problems of eliminating poverty and boosting shared prosperity “at the scale and speed that is required.” Speed and scale were the refrains heard throughout the Spring Meetings last week, particularly when it came to dealing with Africa’s challenges. IMF’s Africa director Abebe Selassie, who told me he “remains optimistic” about sub-Saharan Africa’s resilience, did not sugarcoat the difficult choices some African governments will have to make as debt payments are weighed up against both social and physical infrastructure necessary for development. He also acknowledged that more needed to be done to overcome the funding squeeze his report highlighted. “We typically rely on our richer members to provide us with subsidies and resources that we can then send on to the region but that’s been constrained,” Selassie told me in an interview. “With all the other sources of financing dried up, it’s all the more important that this is available for countries to avoid a grim outlook.” Which brings us back to the need for reforms. Much of the reform that has been proposed so far hasn’t been focused on real development priorities such as debt system reform.  One of the more notable features of the current system, as the chart above shows, is how little influence is wielded by the countries that need the support the most. This is what Ofori Atta meant with his call for a “seat at the table”. Perhaps it’s unsurprising that wealthy countries who foot the bill make the significant decisions in how the system works. But, in an increasingly multipolar world with the rise of other financial partners including China, Turkey, and the Gulf nations among others, African governments who are trying to develop their countries will be less likely to accept the status quo. Room for Disagreement Major reforms will be slow and steady and many of the Bretton Woods institutions’ shareholders will be in no hurry to overhaul the current system, explained Amin Mohseni-Cheraghlou, a macroeconomist at Atlantic Council. “We can expect debt forgiveness and restructuring to happen in some shape and form, especially for low-income economies and those with strategic importance in the continent,” said Mohseni-Cheraghlou. “However, having ‘a seat at the table’ is not going to happen within the next few years because it goes to the core of the governance structure of these Bretton Woods institutions unless major changes in that structure take place, which is very unlikely.” The View from Comoros One of the reasons there have been calls for the reform of the Bretton Woods’ institutions is the growing influence of China, whose own institutions have become major lenders to developing countries. At the same time, the U.S. is seeking deeper engagement with the continent. “Africa should not take sides with one of these blocs,” Mze Abdou Mohamed Chanfiou, the finance minister of Comoros, which is also the current chair of the African Union, told a press conference. “Africa works with both of them; the US and China. Africa doesn’t want to be a continent in the middle of this decoupling.” NOTABLE - Atlantic Council’s Bretton Woods 2.0 Project examines challenges facing the World Bank, IMF, and World Trade Organization in research papers and data visualization to reimagine the governance of international finance institutions.

|